Musulunsi

| Yaɣ sheli | Abrahamic religion |

|---|---|

| Di pilli ni | 631 |

| Di bukaata | Marifa, love for God in Islam, dawah |

| Zuliya wuhibu | الإسلام |

| Siɣili-lana yuli | surrender |

| Ŋun pili | Muhammad |

| Yɛltɔɣa din nyɛ tuma ni dini | laribanchi |

| Kali | Islamic culture, Arab culture |

| Dini be shɛli | Muslim world, worldwide |

| Laɣigu pilibu shee | Hejaz |

| Di duzuɣu shee | Masjid al-Haram, Kaaba, Qibla |

| Foundational text | Alikuraan |

| Di mini ŋa | Alikuraan, Sunnah, hadith, prophetic biography |

| Lahabali maa yaɣa yaɣa | Abrahamic religion |

| Din doli na | Shahada |

| Din doli na | Five Pillars of Islam |

| Taɣi | Arabian mythology, Ancient Semitic religion |

| Nuu tuunbaŋsim balibu | spiritual practice, cult, devotion |

| Ŋun nam | God in Islam |

| Tingbani shɛli din yina | Hejaz |

| Balli tuma bɛi balli yuli | laribanchi |

| Influenced by | Hanif, Judaism, Arabian mythology |

| Kpema | Jibril |

| Ŋun buɣisira | Muhammad's wives, Anabi sɔhibe nima, Salaf, Alikali |

| Commemorates | As-Salam, 99 names of Allah |

| Ŋun bɔhim ŋa nyɛ | Islamic studies |

| Taba laɣim di fiila | humanity, creature, idea, natural environment |

| Location of creation | Maka, Madina, Jerusalem |

| Gɔhiri ni | dhikr, Dua, good works in Islam |

| Tuma ŋɔ maa zaa bɛla URL maa ni | https://corpus.quran.com/qurandictionary.jsp?q=slm, http://www.qurananalysis.com/?q=الإسلام |

| Hasitagi | Islam |

| Nahingbaŋ | monotheism |

| Taarihi bachikpani dalinli | history of Islam |

| Binshɛli din niŋsim | Qalab |

| Practiced by | Musulinsi, ummah |

| Stack Exchange site URL | https://islam.stackexchange.com |

Musulunsi (Islam)[1](/ˈɪzlɑːm, ˈɪzlæm/ IZ-la(h)m;[2] Arabic: ٱلْإِسْلَام, romanized: al-Islām, ar, lit. 'submission [to the will of God]') nyɛla adiini din tam Quran zuɣu ni Anabi Muhammad baŋsibu, ŋun ʒi adiini maa na. Ban doli Musulinsi adiini ka bɛ booni Musulinima, bɛ ni buɣisi shɛba kalinli ka bɛ ni paa niriba 1.9 biliyɔŋ dunia nyaaŋa zuɣu ka nyɛ adiini din galisi pahi buyi Dolodolo adiini nuu yi yi.[3]

Musulinima malila dihitabili ni Musulinsi nyɛla yɛlimaŋli adiini din yuui ka Anabi nima mini tuumba ʒina, n-ti tabili Adam, Anabi Nuhu, Anabi Ibrahima, Anabi Musah, ni Anabi Issah. Musulinima malila dihitabili ni Alikuraani nyɛla yɛltɔɣa shɛli Naawuni ni siɣisi na. Quran nyaaŋa, Musulinima malila dihitabili ni Naawuni ni daa pun siɣisi shɛŋa na puuni, kamani Tawrat (Torah), Zabur (Psalms), ni Injil (Gospel). Bɛ malila dihitabili ni Muhammad n-nyɛ tumo ni yɛlimaŋli ka lahi nyɛ bahigu, ŋun daa pali adiini maa. Anabi Muhammad baŋsibu mini o tuuntumsa, dini n-nyɛ sunnah, di sabimi ka bɛ boli li hadith, nyɛla binshɛɣu din wuhiri Musulinima biɛhigu. Musulinsi adiini saɣimi ti ni Naawuni nyɛla na'gaŋa ka ka kpee. Di yɛliya ni "Sariya karibu Kpalinkpaa" beni ka ban tum tuun viɛla ni nyɛ Alijanda (jannah) ka ban tuma bi viɛli mi nyɛ bɛ ni yɛn dahim shɛba ni buɣim (jahannam). Daantalisi dibaa anu—din nyɛ jama—dini n-nyɛ Musulinsi adiini pɔri ni bɛ tuma (shahada); biɛɣu kulo kam jama (salah); sara malibu (zakat); noli lɔbu (sawm) nolɔri goli ni (Ramadan); ni aʒi chandi (hajj), Mecca. Adiini zalikpani, sharia, shihila biɛhigu yaɣili kam, bini din gbaai banki tuma ni liɣiri biɛhigu hachi zaŋ ti paɣaba ni dobba ni ʒileli. Chu'kara din nyɛ adiini dini n-nyɛ Eid al-Fitr mini Eid al-Adha. Musulinsi adiini luɣa dibaata din gahim n-nyɛ Masjid al-Haram din be Mecca, Prophet's Mosque din be Medina, ni al-Aqsa Mosque din be Jerusalem.

Musulinsi adiini pili la Mecca yuuni 610 CE. Musulinima dihimi tabili din bɔŋɔ di ni daa niŋ ka Anabi Muhammad deei o tuuli surili. Zaŋ chaŋ o kpibu saha, Arabian Peninsula nima pam daa leei la Musulinima. Musulinsi daa yɛligiya yi Arabia "Rashidun Caliphate" ʒaamani ni "Umayyad Caliphate" ŋun daa doli na ka o toontali jendi Iberian Peninsula zaŋ chaŋ Indus Valley. "Islamic Golden Age" saha, di bahi bahindi Abbasid Caliphate saha, Muslinsi tabiibi, daabiligu ni kaya ni taɣada daa tirila tooni. Musulinsi adiini yɛligibu yila di toondaannima kpaŋmaŋa ni na mini daabilgu ni ban daa gindi wuligiri li.

Musulinsi adiini oubu yaɣa buyi din galisi pam n-nyɛ Sunni Islam (85–90%) mini Shia Islam (10–15%). Musulinima n-galisi tingbana pihinu yini ka ni. Kamani Musulinima vaabu 12% dunia nyaaŋa zuɣu m-be Indonesia, Musulinima ni galisi tiŋgbani shɛli ni; vaabu 31% m-be South Asia; 20% m-be Middle East–North Africa; ka vaabu 15% be sub-Saharan Africa. Musulinima lahi be Americas, China, niEurope. Musulinima nyɛla ban yɛligiri yom pam.

Bachi maa ni pili shɛm

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Larigu ni, Islam (Arabic: إسلام, lit. 'zaŋ maŋa ti [Naawuni]')[4][5][6] nyɛla nolini bachinamdili "Form IV" din yina bachinŋdli ni سلم (salama), din yina "triliteral root"س-ل-م (S-L-M), din nam bachi bɔbigu pam din yari zaŋ maŋa ti yɛltɔɣa, tiligibu, ni suhudoo.[7] Adiini yuligu puuni, di nyɛla zaŋ maŋa zaa ti Naawuni.[8]Muslim (مُسْلِم), bachi din zani ti ŋun doli Musulinsi,[9] di lahi nyɛla din zaani tiri "ŋunzaŋdi o maŋa tiri (Naawuni)" bee "bee ŋum baligi o maŋ n-ti (Naawuni)". Hadith of Gabriel ni, Islam lahi nyɛla din chani imān (yɛlimaŋ tibo), ni ihsān (dede).[10][11]

Taarihi ni Musulinsi adiini maŋmaŋa yuli n-daa na booni Mohammedanism Siliminsili yɛlibu ʒaamani. Lala bachi ŋɔ nyɛla bɛ ni tooi bi lahi dii booni shɛli, ka di lahi ŋmani din mali taali, di wuhirila ninsala, ka pani Naawuni, di nyɛla din tam' Musulinsi adiini sunsuuni.[12]

Articles of faith

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Musulinsi aqidah malila dihitabili daantalisi dibaa ayɔbu: Naawuni, Malaikanima, baŋsibu, anabi nima,Kum ni neebu, ni Naawuni ni zali shɛli.[13]

Musulinsi adiini tamla tawḥīd (Arabic: توحيد) zuɣu, Naawuni gaŋ'tali. Di tooi nyɛla bɛ ni tɛhi ni shɛli nyɛla adiini yin dolibu, amaa ka lahi wuhiri ni Naawuni be luɣili kam Musulinsi adiini baŋsibu ni.[14][15] Naawuni ka so zaŋ ŋmahindi ka lahi ka kpee kamani Dolodolo ni mali yɛla dibaa ata shɛm, ka binshɛɣu zaŋ ŋmahindi Naawuni nyɛ buɣa jambu, bɛ ni boli shɛli shirk. Naawuni n-nyɛ binnamda duuma ka o ku tooi baŋ naai. Dini n-nyɛ, Musulinima bi mali Naawuni maɣisiri binshɛɣu. Amaa bɛ mali yuya pam booni Naawuni, din niŋ bayana n-nyɛ Ar-Rahmān (الرحمان) ka di gbunni nyɛ "ŋun zori sokam nambɔɣu," ni Ar-Rahīm (الرحيم) ka di gbunni nyɛ "Ŋun gahindi zori nambɔɣu" ka bɛ tooi karimdi li Quran yaɣa pam tuuli.[16][17]

Musulinsi saɣimi ti ni binshɛɣu kam din be dunia nyɛla Naawuni yiko ni, "Niŋma ka di shiri niŋ[lower-roman 1][4] ni ka nambu daliri nyɛ o jama zuɣu.[18] O nyɛla o maŋmaŋa Naawuni[4] aka so ka o sunsuuni, kamani ŋun yɛn zaŋ lahabali ti paagi O. Naawuni yɛla tebu nyɛla Taqwa. Allāh nyɛla bachi din ka zaɣ'bɔbigu bee m-buɣisiri paɣa bee doo ka sokam mali li m-booni o, ka ʾilāh (إله) zani ti wuni bihi zaa.[19]

Malaikanima

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Malaikanima (Arabic: ملك, malak) nyɛla bɛ ni buɣisi shɛba Quran[20] mini hadith ni.[21] Bɛ nyɛla bɛ ni buɣisi ka shɛba nambu daliri nyɛ bɛ jam Naawuni ka yari Naawuni yɛltɔɣa, ka sabiri sokam tuma, ka deei ninsala nyɛvuli o kpibu saha. Bɛ buɣisiba mi ka bɛ Namba 'neesim' (nūr)[22][23][24] bee 'buɣim' (nār) ni.[25][26][27][28] Musulinsi malaikanima nyɛla bɛ ni buɣisi ka shɛba mali kpunkpama ni nahingban shɛŋa.[29][30][31][32] Bɛ nahingbana shɛŋa n-nyɛ bɛ ka suhuyurilim, kamani dibu mini nyubu.[33] Bɛ shɛba kamani, Gabriel (Jibrīl) mini Michael (Mika'il), nyɛla bɛ i boli shɛba yuya Quran ni. Malaikanima mali nuu timbu ni Mi'raj sabbu baŋsim ni, luɣ'shɛli Muhammad mini malaikanima ni laɣim taba o zuɣusaa chandi ni.[21] Malaikanima shɛba yuya lahi nyɛla din be adiini sabiri shɛŋa ni.[34]

Kundunima

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Musulinsi kundu din daŋ na nyɛla Quran. Musulinama malila dihitabili ni Quran nyɛla Naawuni ni daa siɣisi shɛli n-ti Muhammad na, ka di nyɛla malaika Gabriel n-daa zaŋli na, siɣim bushɛm zuɣu yuuni 610 CE[35][36] mini 632, yuun shɛli Muhammad ni kpi.[37] Muhammad ni daa be o nyɛvuli ni, bɛ ni daa siɣisi Alikuraani yaɣ'shɛŋa ŋɔ na daa nyɛla o nyaandoliba ni sabi shɛli sɔŋ, amaa di tuuli wuligibu daa nyɛla noli ni mini gbaai niŋ zuɣu ni.[38] Quran pirigila malila suurinima kɔbigu ni pia ni anahi (sūrah) ka di laɣim tamab mali aayanima tusaayɔbu ni kɔbishii ni pihita ni ayɔbu (āyāt).Tuuli suurinima, daa siɣisimi na Makkah ka ta dabodabo yaɣa, ka Medinan suurinima din daa doli na jendi biɛhigu mini Musulinsi adiini ni saɣiti shɛli Musulinima ni.[4][39] Musulinima sariya ŋmaariba hadith ('accounts'), bee Muhammad biɛhigu din sabi sɔŋ, ni di laɣim tum ni Quran ka tabi sɔŋ ni di kahigibu. Alikuraani alizama nyɛla bɛ ni boli shɛli tafsir.[40][41] N-ti pahi d adiini yɛla din kpa talahi ni, Quran n-nyɛ "Arabic literature" din niŋ kasi,[42][43] ka mali nuu timbu ni "art" mini Arabic balli.[44]

Musulinsi lahi yɛliya ni Naawuni kahigila ashiya, bɛ ni boli shɛli wahy, n-ti anabinima balibu pam. Amaa, Musulinsi wuhiya ni kundunima din daa daŋ maa na, kamani Tawrat (Torah) ni Injil (Gospel), nyɛla din wurim—di ni tooi nyɛ di kahigibu, di sabbu, bee di zaa,[45][46][47][48] ka Alikuraani (lit. 'karimbu') nyɛ bahigu, ni Nawwuni yɛltɔɣa din bi taɣi.[39][49][50][51]

Anabinima

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Anabinima (Arabic: أنبياء, anbiyāʾ) nyɛla bɛ ni dihitabili ni Naawuni daa piigi shɛba ni bɛ wuligiri o yɛltɔɣa. Lala Anabinima ŋɔ shɛba daa ʒila kundu pala na ka bɛ booni ba "tuumba" (رسول, rasūl).[53] Musulinima malila dihitabili ni Anabinima nyɛla ninsalinima. Bɛ malila dihitabili ni Anabinima zaa yɛlila Musulinsi adiini yɛltɔɣa – Naawuni ni bɔri shɛli dolibu – n-tɔɣisiri tiri tiŋgbana din daa gari ha, lala ŋɔ nyɛla dihitabili din be adiini bɔbigu ni. Quran kali anabinima pam ban be Musulinsi adiini ni, n-ti tabili Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses ni Jesus, ni ban pahi pahi.[4][54] Anabinima lahabali din ka Quran ni nyɛla din be Qisas al-Anbiya (anabinima lahabaya ni).

Musulinima malila dihitabili ni Muhammad n-nyɛ anabinima bahigu ka Naawuni tim na ("Seal of the prophets") ni o ti wuligi Musulinsi adiini din pali.[55][56] Musulinsi adiini ni, bɛ booni la Muhammad ni daa be biɛhi shɛli sunnah (literally "trodden path"). Musulinima tu ka bɛ tumdi Muhammad tuuntumsa biɛɣu kulo kam, ka sunnah maa nyɛ din kahigiri Quran.[57][58][59][60] Lala shɛhira ŋɔ nyɛla din gu m-be hadith ni, din yari o nolini yɛltɔɣa, tuuntumsa, ani ninsalisili biɛhigu. Hadith Qudsi nyɛla hadith yaɣ'shɛli, din yari Anabi Muhammad ni yɛli Naawuni maŋmaŋa ni daa kuliyɛli yɛltɔɣa shɛŋa ka di ka Quran ni. Hadith chanimi ni yɛla dibaa ayi: ban tɔri neeri lahabali, ka bɛ booni ba sanadTɛmplet:Broken anchor, ni yɛltɔɣa ni kuli nyɛ shɛm, ka di mi nyɛ matn. Soya din waligiri hadiths yɛlimaŋ'tali zooya, ka "grading scale" din niŋ bayana nyɛ din niŋ "dede" bee "viɛnyɛla" (صحيح, ṣaḥīḥ); "dede" (حسن, ḥasan); "zaɣ'gbariŋ" (ضعيف, ḍaʻīf), ni din pahi pahi. Kutub al-Sittah nyɛla bukunima dibaa ayɔbu din laɣim taba, ka nyɛ lahabali shɛli din wuligi ka nyɛ yɛlimaŋli Sunni Islam ni. Din ni shɛli n-nyɛ Sahih al-Bukhari, ka Sunni nima tooi nya ka dini n-nyɛ yɛlimaŋli dini Quran nuu yi yi.[61] Hadiths din lahi pahi ka nriba pam mili n-nyɛ "The Four Books", ka Shianima nya ka dini n-nyɛ hadiths maŋli.[62][63]

Kum ni neebu mini sariya karibu

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Dihitabili ni "KUm ni neebu dabisili" bee Yawm al-Qiyāmah (Arabic: يوم القيامة) gba nyɛla Musulinima ni dihi shɛli tabili. Dihitabili n-nyɛli ni Qiyāmah yiɣisibu nyɛla Naawuni ni pun zali shɛli, amaa ka ninsali bi mi li.[64][65][66]

Dunia yi ti yiɣisi, Musulinima malila dihitabili ni bɛ yɛn karila ninsalinima zaa sariya ni bɛ ni tum tuun viɛli shɛŋa mini zaɣi be shɛŋa ka kpe Jannah (paradise) bee Jahannam (buɣim) ni.[67]Quran suurili al-Zalzalah buɣisila ŋɔ ni: "Ni ŋun tum zaɣ'viɛli ka di pɔri ka wula ni deei di tarili. Ka ŋun tum zaɣ'biɛɣu biɛla gba ni deei di samyoo." Quran kali taya pam din ni tooi ʒi nira kpe buɣim ni. Amaa, Quran neeli ni Naawuni ni che ŋun bɔ champaŋ taali o suhu yi bɔra. Tuun viɛla, kamani sara, jama, ni binkɔbiri nambɔɣu zɔbu[68] nyɛla Naawuni ni yɛn ti shɛba alijanda. Musnyɛla alijanda ka di nyɛ nyaɣisim shee alibarika, ka Quran buɣisi di nahingbana.[69][70][71] Yawm al-Qiyāmah nyɛla din be Quran ni ka nyɛ Yawm ad-Dīn (يوم الدين "Adiini dabisili");[lower-roman 2] as-Sāʿah (الساعة "Naabu saha");[lower-roman 3] ni al-Qāriʿah (القارعة "The Clatterer").[lower-roman 4]

Naawuni ni pun zali shɛŋa

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Naawuni ni zali shɛŋa Musulinsi adiini ni (Arabic: القضاء والقدر, al-qadāʾ wa l-qadar) gbunni nyɛla binshɛɣu kam, din viɛli bee din be, nyɛla Naawuni yiko. Al-qadar, gbunni "yaa", din yimina yɛltɔɣa din nyɛ "n-zahim" bee "laasabu malibu" puuni.[72][73][74][75] Musulinima tooi yarila lala dihitabili ŋɔ ni "In-sha-Allah" (Arabic: إن شاء الله) ka di gbunni nyɛ "Naawuni yi saɣi" bɛ yi yɛri dahinshɛli din be tooni yɛltɔɣa.[76]

Taarihi

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Muhammad and the beginning of Islam (570–632)

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Musulinsi adiini ni wuhi shɛm, bɛ daa dɔɣila Muhammad Mecca yuuni 570 CE ka o daa niŋ kpibiga ka na nyɛ bia. O ni daa zoorina ka nyɛ daabia, sokam daa mi ka o nyɛla yarida lana (Arabic: الامين). O daa ti niŋ o ni tumdi n-tiri so amiliya, paɣa ŋun daa niŋdi daabiligu ka o yuli booni Khadija.[77] Yuuni 610 CE, miisim din daa kana ni buɣa mɔŋbu Mecca, Muhammad daa kuli" Cave of Hira" ni zoli yuli booni Jabal al-Nour ni, ka di baɣi Mecca. O zolɔŊ ŋo ni benibu ni nka bɛ daa siɣisi Quran yaɣ'shɛli tuuli na n-ti ti o, malaika Gabriel n-daa zaŋli na.[78] Muhammad zolɔŋ ŋɔ ni kpebu ŋɔ mini Quran siɣisibu na nyɛla bɛ ni buɣisi shɛli "Yuŋ din mali yaa" (Laylat al-Qadr) ka di nyɛ din mali bukaata Musulinsi adiini taarihi ni. O yuun pishi ni ayi din daa pahiri ni, yuun pihinahi zaŋ chana, Muhammad daa nyɛla ŋun deeri waahi Naawuni sani, ka nyɛ malaika bahigu Naawuni ni tim na ninsalinima sani.[45][46][79]

Lala saha ŋɔ ni, o ni daa be Mecca, Muhammad daa na wuligirila adiini ashilo ni pɔi ka daa naan yi ti yihili saolo ni, ka mɔŋdi o wumdiba ni bɛ cheli buɣa ka jamdi Naawuni gaŋ ko. Tuuli ban daa dolisi pam daa nyɛla paɣaba, faranima, saamba, ni daba kamani tuuli ŋun moli jiŋli muezzin Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi.[81]Meccanima daa nyami ka Muhammad saɣindi bɛ ninsalisili ni o ni niŋdi waazu zaŋ chaŋ Naawuni gaŋa dolibu polo la ka bɔhiri nandaamba mini daba bɔhisi kadama bɛ nyɛla ban diri anfaani Kaaba buɣa ni.[82][83]

Mecca nima ni daa kuri Muslinima yuun pia ni ayi nyaaŋa, Muhammad mini o nyaaŋa daa niŋ Hijra ("yinlooi") yuuni 622 n-kuli tiŋa yuli booni Yathrib (zuŋɔ din pa nyɛ Medina). Din ni, ni Medinan ba dolisi ( Ansar) ni ban yi Mecca labi ni (Muhajirun), Muhammad ni daa be Medina o daa pilila o maŋmaŋa siyaasa ni adiinilaɣimbu. Medina zalisi nyɛla Medina bala zaa ni daa dihi nuu shɛli ni. Lala adiini saɣiti ŋɔ daa nyɛla din yɛn sɔŋsi ka zalisi maa tum tuma Musulinima sani ni ban pa Musulinima ka lahi guba ka barina din yɛn yi sambani ni na ku paai Medina.[84] Meccanima daa lu Battle of Badr ni bɛ mini Musulinma tuhibu ni yuuni 624 ka daa labi tuhi Battle of Uhud[85] pɔi ka daa naan yi bi tooi di nasara Medina "Battle of the Trench" ni (March–April 627). Tuuni 628, "Treaty of Hudaybiyyah" daa nyɛla Mecca mini Musulinima ni daa dihi nuu gbana ti saɣiti shɛli, amaa ka Mecca nima daa yiɣisi li yuma ayi nyaaŋa. Di ni daa niŋ ka bala pam dolisi labi Musulinsi adiini ni, Mecca nima daabiligu soya daa nyɛla Musulinima ni ŋari shɛli.[86][87] Zaŋ kana yuuni629 Muhammad daa di nasara Mecca, ka zaŋ chaŋ o kpibu saha yuuni 632 (yuun pihiyɔbu ni ayi ni) o daa laɣim laArabia bala ka bɛ doli adiini yini.[88][35]

Early Islamic period (632–750)

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Muhammad daa kpila 632 ka tuuli fadiriba maa, bani n-nyɛ Caliphs – Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman ibn al-Affan, Ali ibn Abi Talib ni saha shɛŋa ka Hasan ibn Ali gba beni[89] – Sunni Musulinsi ni bɛ booni ba la al-khulafā' ar-rāshidūn ("Rightly Guided Caliphs").[90] Zuliya shɛŋa daa chela Musulinsi adiini ka zaŋ bɛ maŋsi ti pahi toondaanninma ban daa zaŋ bɛ maŋa lee Anabinima ni amaa ka Abu Bakr daa kpehiba nuuni Ridda tɔbu ni.[91][92][93][94][95] Jews mini Dolodolo nima shɛba, bɛ ni daa kuri bɛ hɛba daa tooi sɔŋdi Musulinima ka bɛ deeri bɛ tiŋgbana,[96] ka di zuɣu daa che ka toondaannima ŋɔ yɛligiri Persian mini Byzantine tiŋgbana ni.[97][98][99][100] Bɛ daa piigi Uthman yuuni 644 ka o kubu daa che ka bɛ daa piigi Ali Caliph ŋun daa pahi buyi. Tuuli sabiila nima tɔbu ni, Muhammad pakoli, Aisha, daa sahila tɔbu bihi bahi Ali zuɣu, ni o bɔhi Uthman kpibu beri, amaa ka daa kɔŋ nasara "Battle of the Camel" ni. Ali daa moya ni o yihi Syria zuɣulana, Mu'awiya, bɛ ni daa nya ka so mali korinfahili. Ka Mu'awiya daa moli tɔbu bahi Ali zuɣu ka daa kɔŋ nasara Battle of Siffin tɔbu ni. Ali ni daa mali niya ni o bɔ maligu daa nyɛla din yiɣisi Kharijites suhuri, dama bɛ daa ʒimi ni nira yi bi tuhi taali tumda, Ali gba tumla taali maa. Kharijites daa tuhiya ka daa kɔŋ nasara "Battle of Nahrawan" ni amaa Kharijite daa ti ku Ali. Ali bi'dibiga, Hasan ibn Ali, ka bɛ daa piigi Caliph ka bɛ daa dihi nuu suhudoo gbana ni di gu ka taɣi tooni ha zabili, ka daa lahi zaŋ Mu'awiya niŋ naa labisi Mu'awiya ka daa bilahi piigi ŋun yɛn zani o zaani.[101] Mu'awiya daa piligi Umayyad dynasty ni o dapali Yazid I piibu o fa'dira, ka di daa lahi yiɣisi sabila tɔbu din pahiri buyi. "Battle of Karbala" ni, Husayn ibn Ali daa nyɛla Yazid' nyaaŋ ni ku so; Shia nima teerila di yɛla yuuni kam tum di ni niŋ. Sunnanima, Ibn al-Zubayr daa gari tooni n-ŋme nangbankpeeni ni "dynastic caliphate," ka daa kɔŋ nasara siege of Mecca ni. Lala kpamli zabili ŋɔ nyɛla din yɛn duhi Sunni-Shia schism zuɣusaa,[102] ka Shia mali dihitabili ni kpamli bela Muhammad zuliya ni zaŋ yi Ali sani, bɛ ni boli shɛli ahl al-bayt.[103] Abu Bakr n-daa gari tooni ka bɛ laɣim Quran taba. Caliph Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz n-daa kpa di komitii," The Seven Fuqaha of Medina",[104][105] ka Malik ibn Anas sabi tuuli Musulinsi adiini bukunima puuni yini.[106][107][108] Kharijites daa dihimitabili ni larigibu ka zaɣ'biɛɣu mini zaɣ'viɛlli sunsuuni, ka Musulimi ŋun tum taali titali yɛn nyɛ ninvuɣ'so ŋun yi dihitabili ni. Bachi din nyɛ "kharijites" gba nyɛla din yɛn zani ti dahinshɛli laɣinsi kamani ISIS.[109] Murji'ah tɛha nyami ni Naawuni ko n-ni tooi wuhi daadam tuun viɛla ni nyɛ shɛli. Di zuɣu, ban tumdi tuun biɛri ni tooi nyɛ ban bi doli so viɛlli, amaa ka di pala bɛ bi dihimitabili.[110] Din bɔŋɔ nyɛla din be Musulinsi adiini dihitabili ni.[111]

"Umayyad dynasty" daa deei la Maghreb sulinsi, Iberian Peninsula, Narbonnese Gaul ni Sindh.[112] "Umayyads" maa daa nyɛla ban niŋ wahala ni yɛlimaŋ tali ka zaŋ bɛ yaa zaa baɣi linjimanima ni.[113] Tum di ni daa niŋ ka jizya farigu nyɛ farigu shɛli ban bi ti Musulinsi adiini ni yori shɛli la ka di zuɣu yihiba linjimanima tuma tumbu ni, "Umayyads" maa daa zaɣisi Arab ban daa dolisiri yɛla baŋbu, pirimla di ni daa bɔri bɛ ni nyari ariziki shɛli la.[111] Dini daa niŋ ka Rashidun Caliphate zaɣa zaa daa be biɛhigu ni maa, ka Umar daa tom lahi bɔri kpɛm ka ni gbubi shɛli tiligibu,[114] Umayyad nachintɛrtɛri daa nyɛla yɛlimaŋ tiriba suhu ni daa bi piɛli zaŋ chaŋ shɛli polo.[111] Kharijites daa zaŋla Berber Revolt gari tooni, ka di zuɣu daa che ka Musulinima Caliphate tiŋgbana deei maŋsulinsi. Abbasid Revolution ni, ban daa Arab nima ban dolisi (mawali), Arab nam zuliyanima daa nyɛla Umayyad nam zuliyanima ni daa daai shɛli luhi, ka Shi'a nima shɛba daa ŋme n-yiɣisi Umayyads maa, ka daa pili tiŋgbana nima pam laɣimbu "Abbasid dynasty" yuuni 750.[115][116]

Classical era (750–1258)

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Al-Shafi'i yimina ni so'chibiga din wuhiri hadith zaɣ'maŋtali.[117] Abbasid piligu saha, baŋdiba kamani Muhammad al-Bukhari mini Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj n-daa laɣim Sunni hadith zuɣuri ka baŋdiba kamani Al-Kulayni mini Ibn Babawayh mi laɣim Shia hadith zuɣuri. Sunnanima anahi Madh'habs, Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki, ni Shafi'i, daa nyɛla bɛ ni me shɛli tam Abū Ḥanīfa, Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Malik ibn Anas ni al-Shafi'i baŋsibu zuɣu. Lala n-lahi nyɛli, Ja'far al-Sadiq baŋsibu n-nyɛ din nam Ja'fari jurisprudence. 9th century saha, Al-Tabari daa naa lahabali din dalim Quran sabbu, Tafsir al-Tabari, din niŋ shɛhira lahabali din kpa talahi Sunni Musulinsi adiini ni. [118][119]

Saha ŋɔ ni, adiini yɛlimuɣisira, daa nyɛla bɛ ni kpe shɛli tuma ni, ka Hasan al Basri daa be di tooni dimini Naawuni m-mi niriba tuuntumsa maa zaa yoli.[120][lower-alpha 1] Greek haŋkali zilinli lana daa niŋla nimmohi ni shikuru tɛhi shɛli bɛ ni boli Muʿtazila, ka daa kpaŋsi "free-will" shɛli Wasil ibn Ata ni daa pili.[122] [123] Caliph Al-Mu'tasim daa niŋla vihigu ni Ahmad ibn Hanbal bɛ ni daa mi ka so zaɣisi Muʿtazila tɛha zani tuhi.[124] [125][126]

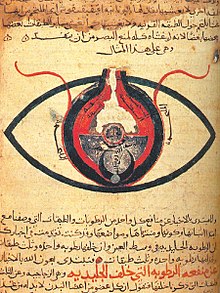

Saha shɛŋa bɛ booni la lala ʒaamani ŋɔ"Islamic Golden Age".[127][128][129][130][98] Musulinsi adiini tabiibi nasara dibu nyɛla din gili yaɣa pam n-ti tabili medicine, mathematics, astronomy, ni agriculturen-ti pahi kamani physics, economics, engineering ni optics.[131][132][133][134] Avicenna daa nyɛla ŋun gari tooni ni "experimental medicine",[135][136] ni o "The Canon of Medicine" daa nyɛla "medical" sabbu din zani di naba zuɣu musulinsi ni mini Europe yuun gbaliŋ. Rhazes n-daa nyɛ tuuli ŋun baŋ doro din nyɛ smallpox mini measles.[137] Gɔmnanti tuuli ashibitinima lala saha daa ti dɔɣite nima shɛhira gbana.[138][139] Ibn al-Haytham ka bɛ boli ʒaamani tabiibi ba ka bɛ tooi booni o "dunia tuuli yɛlimaŋli tabiibi lana."[140][141][142] Injiniya tali ni, Banū Mūsā mabiligu ŋun pebiri niŋdi n-to kalimboo ka bɛ yɛli ni ŋuni n-daa yina ni tuuli maʒini parigu.[143] Laasabu malibu ni, "algorithm" nyɛla bɛ ni zaŋ Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi yuli ti shɛli, ŋun yihi algebra na, ka bɛ zaŋ di yuli ti o buku din nyɛ al-jabr, ka shɛba mi yina ni "function".[144] Gɔmnanti yorila tabiibi tuuntumdiba ban guuri yim zuŋɔ.[145] Guinness World Records baŋla University of Al Karaouine yɛla, din daa pili yuuni 859, dunia university kurili din tiri shɛhira gbaŋ din nyɛ "degree".[146] Ban pa Musulinima pam, kamani Christians, Jews ni Sabians,[147] nyɛla ban mali nuu timbu ni Musulinsi adiini nini neebu yaɣa pam ni,[148][149] ka baŋsim tuma yaɣili din yuli booni House of Wisdom kpuɣi Dolodolo mini Persian baŋdiba ka bɛ lɛbigiri sabbunima larigu ni ka yɛligiri baŋsim pala.[150][147][151]

Pre-Modern era (1258–18th century)

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Musulinsi daabilugu tuma ni Sufi tuuntumsa ni,[152] Musulinsi adiini yɛligimi chaŋ luɣ'shɛŋa[153] ka Musulinima dee kaya ni taɣada pla.

Ottoman Empire ni, Musulinsi yɛligimi chaŋ Southeast Europe.[154] Musulinsi adiini ni kpebu nyɛla adiini bɔbigu laɣmbu,[155] kamani Muhammad yɛltɔɣa ni yina Hindu salima ni shɛ.[156] Muslim Turks laɣim la Turkish Shamanism dihitabilinima ni musulinsi.[lower-alpha 2][158] Musulinima ban be Ming Dynasty China ban daa yina tuuli yaakoronima ni, saha shɛŋa zaŋ chaŋ zalisi zalibu ni,[159] Chinese yuya ni kaya ni taɣada paŋbu ni Nanjing daa niŋla Musulinsi adiini biɛhigu shee.[160][161]

Kaya ni taɣada taɣibu shɛhira daa nyɛla Arab yiko taɣibu ni Abbasid Caliphate Mongol ni daa saɣim nyaaŋa.[162] Musulinima Mongol Khanates din be Iran mini Central Asia daa di anfaani ni East Asia kaya ni taɣada tabi ni kp ni kpebu Mongol sulinsi saha ka daa nya lɛbiginsim pam ni Arab kpaŋmaŋa ni, kamani Timurid Renaissance, Timurid dynasty saha.[163] Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274) daa tɛhimi gbaai laasabu mali polo ka nangbaankpeeni daa ti kana ni Copernicus daa zaŋli mi m-pahi o "heliocentric model" ni,[164] ka Jamshīd al-Kāshī pi buɣisibu ku gari yuun kɔbigu ni pihinii.[165]

Malifa ti'zima tɔb'bina malibu nyaaŋa, Musulim tiŋgbana pam daa ʒinimi miri "gunpowder empires", din bɔŋɔ daa nyɛla din gili tiŋgbana pam ni. Ottoman dynasty daa deei la Ottoman Empire toondaan' tali ka o deebu daa niŋ yaa yuuni 1517 di ni daa niŋ ka Selim I daa leei Mecca mini Medina naa.[166] Shia Safavid dynasty daa yiɣisi zani deei yaa yuuni 1501 ka daa ti deei Iran zaa.[167] South Asia tiŋgbani ni, Babur daa kpa Mughal Empire.[168]

"Mevlevi Order" mini "Bektashi Order" daa mlila biɛhigu ni sultans,[169] kamani "Sufi-mystical" ni "heterodox" mini "syncretic" so'dolisi ni Musulinsi adiini ni daa kpaŋsi la.[170]Dakulo kam nahingu ni "Safavid conversion of Iran" zaŋ chaŋ Twelver Shia Islam din be Safavid Empire daa che ka Twelver sect daa nyɛ din du zuɣusaa ni Shia Musulinsi ni. Persian yaakoro niŋdiba ban daa kuli South Asia, ka nyɛ tiŋgbani suriba, daa nyɛla ban sɔŋsi yɛligi Shia Musulinsi adiini, ka di daa nam Shia nima pa Iran polo tiŋ'shɛŋa ni.[171] Nader Shah, ŋun daa ŋme n-yiɣisi Safavids, daa moya ni o kpaŋsi biɛhigu ni Sunna nima ka di nyɛla o daa malila Twelverism pahiri Sunni Musulinsi ni ka di nyɛ "madhhab" din pahi anu, ka bɛ boli li Ja'farism,[172] ka di daa bɛ tooi nya taɣidee Ottomans.[173]

Modern era (18th–20th centuries)

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

14th century piligu, Ibn Taymiyya daa kpaŋsirila "puritanical" Islam balishɛli,[174] ka zaɣisiri adiini so'dolisi din niŋ soochi,[174] ka bɔri ni bɛ yooi itjihad dunoya gari baŋdiba tɔɣisibu din be zimsim ni.[175] o daa bɔri ni bɛ tuhi o ni boli shɛba "heretics",[176] amaa o sabbunima tumla tuma saha shɛli o ni daa be o nyɛvuli ni.[177] 18th century saha, Arabia tiŋgbani ni, Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab, ni Ibn Taymiyya mini Ibn al-Qayyim tabi sɔŋ puuni, bɛ daa kpa laɣingu shɛli bɛ ni daa boli Wahhabi ni bɛ labi o ni daa nya ka shɛli pa Musulinsi adiini ni.[178][179] O daa filim Musulinsi adiini yɛltɔɣa shɛŋa, kamani Anabi Muhammad (S.A.W) gballi kaabu, ka yɛli ni di nyɛla din yoli kana ka nyɛ taali[179][180] ka saɣim buɣi kuɣa mini tihi, Sufi buɣa, Anabi Muhammad mini o nyaaŋa gbala ni Husayn gballi din be Karbala, Shia daantali kpeeni shee.[180][181][182] O daa naai la noli ni Saud zuliya, ka zaŋ kana yuuni 1920s, ka bɛ daa deei luɣ'shɛli din pa yɛn nyɛ Saudi Arabia.[180][183]Ma Wanfu mini Ma Debao daa kpaŋsi "salafist movements" 19th century kamani Sailaifengye China dini daa niŋ ka bɛ yi Mecca labina amaa ka bɛ daa kuriba ka di zuɣu che ka bɛ bi yuri ka sɔɣiri Sufi laɣinsi.[184] Laɣin shɛŋa daa labiri mi niɣindi Sufism amaa ka bi kariti li, ka Senusiyya mini Muhammad Ahmad zaa daa lɔri tɔbiri ka zaani tiŋgbana Libya mini Sudan zaa.[185] India tiŋgbani ni, Shah Waliullah Dehlawi daa moya ni o bo maligu niŋ Sufism nima sunsuuni ka daa sɔŋsi "Deobandi movement".[186] Deobandi movement ŋɔ dolibu ni, Barelwi movement gba daa kpaya ka nyɛ laɣingu din galisi, ka zaniti Sufism ka niɣindi di tuuntumsa.[187][188]

Musulinsi siyaasa daa pili tiŋgbani ni donibu 1800s piligu, di bahi bahindi zaŋ ŋmahindi Europe yahinima ban pa musulinima zaŋ ŋmahindi taba. Piligu ha, 15th century, Reconquista daa di nasara ni ni Musulinima karibu Iberia. Zaŋ chaŋ 19th century, British East India Company daa zali Mughal dynasty India tiŋgbani ni.[189] [190] Musulinsi adiini taɣibu, Western baŋdiba ni daa tuui boli shɛli Salafiyya, daa taɣimi deei ʒaamani binyɛra din kpa talahi. Ban daa be lala laɣingu ŋɔ tooni shɛba n-nyɛ Muhammad 'Abduh mini Jamal al-Din al-Afghani.[191] Abul A'la Maududi daa sɔnmi kpaŋsi ʒaamani Musulini siyaasa.[192][193] [194]

Ottoman Empire daa kpihim ya World War I nyaaŋa, Ottoman Caliphate daa kpihim ya yuuni 1924[195] ka Sharifian Caliphate din daa dolina gba daa lu yom,[196][197][198] ka Musulinsi pa beni ka ka toondana.[198] Pan-Islamists daa moya ni bɛ laɣim Musulinima nangbani yini ka niŋ zaɣa ni bɛ yaa zoobu tiŋgbana ni, kamani pan-Arabism.[199][200] Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), Musulinima ni galisi tiŋgbani shɛŋa ni n-daa be din ni, di daa kpala yuuni 1969 bɛ ni daa nyo Al-Aqsa Mosque din be Jerusalem nyaaŋa.[201]

Daabiligu daa ʒi Musulinsi kpe tiŋgbani yaɣa pam. Musulinima pam daa niŋ yaakoro (di yaa daa nyɛla India mini Indonesia) zaŋ kuli Caribbean, ka di zuɣu daa che ka Musulinima galisim daa be Americas.[202] Yaakoro niŋ yi Syria mini Lebanon nyɛla din pahi ka Musulinima galisi Latin America.[203] Sub-Saharan Africa fɔŋ leebu mini daabiligu kpaŋsibu nyɛla din ʒi Musulinima na ka bɛ ti ʒini tiŋgbani yaɣ'pala ka wuligi Musulinsi adiini,[204] ka Musulinima kalinli pahi bini din gbaai yuuni 1869 zaŋ chaŋ yuuni 1914.[205]

Contemporary era (20th century–present)

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Ban gari ʒaamani Musulinsi tooni kpaŋsila Musulinima siyaasa kamani "Muslim Brotherhood" ni paati shɛŋa din pahi Arab yaɣili,[206][207] ka di tum viɛnyɛla piibu piibu nyaaŋa kamani Arab Spring,[208] Jamaat-e-Islami din be South Asia mini AK Party, ka tahi vuhim na Turkey yuun gbaliŋ. Iran tiŋbani ni, nyɛla ban bo naa ʒili Musulinsi adiini tiŋgbani shɛli ni. Ban pahi kamani Sayyid Rashid Rida birigila adiini ʒaamani zalisi[209] ka saɣiritiri o ni boli shɛ "Western influence".[210] Laɣingu din nyɛ Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant nyɛla ban yɛn mɔ n-nam saha ŋɔ salima liɣiri ka di niŋ bɛ liɣiri.[211]

Musulinsi siyaasa laɣinsi nyaaŋa, 20th century saha Turkey, linjimanima daa ŋmerimi ni bɛ yiɣisi gɔmnantinima ban nyɛ Musulunima, lala n-nyɛli ka di daa lahi niŋ Tunisia.[212][213] Saudi Arabia tiŋgbani ni, tiŋgbani maa adiini sɔŋsikm daa nyɛla yini[214] ka, Egypt tiŋgbani ni, tiŋgbani maa zaa Al-Azhar University, din daa na nyɛ tiŋgbani maa kukoli di ʒi di gama zuɣu lihibu.[215] Salafism daa pilila Middle East.[216] Saudi Arabia daa niŋdila kampee tuhiri "revolutionary Islamist movements" din daa be Middle East, zaŋ dalim Iran.[217]

Musulunima ni daa bi galisi zuliya shɛŋa ni daa nyɛla bɛ ni kuri shɛba.[218] Ban daa be di tooni n-daa nyɛ tiŋbihi ban daa mali kpeŋ kamani Khmer Rouge, ban da nyɛ ka bɛ nyɛ bɛ dimba ka di daliri nyɛla bɛ daa adiini nyɛla din che ka bɛ yi bɛ ko ka che salo maa zaa,[219] Chinese Communist Party din be Xinjiang[220] ni tiŋgbani yahinima kamani Bosnian genocide saha.[221] Myanmar linjimanima Tatmadaw miricho Rohingya Muslims daa nyɛla bibiɛlim zaŋ ti ninsalisili, UN mini Amnesty International zalisi ni,[222][223] ka OHCHR Fact-Finding Mission daa nya ka genocide, ethnic cleansing, ni din pahi pahi gba nyɛ bibiɛlim zaŋ ti ninsalisili.[224]

Ninneesim zaŋ kana lahabali wuligibu toontibo ni nyɛla din wuligi adiini baŋsim pam. Hijab zaŋ ku bukaata nyɛla din niŋ bayana[225] ka Musulunsi adiini baŋdiba shɛba mori ni bɛ waligi Musulunsi adiini dihitabilinima ka che kaya ni taɣada.[226] Zuliya shɛŋa ni, lala lahabali ŋɔ wuligibu nyɛla din tahi "televangelist" waazu niŋdiba na, kamani Amr Khaled.[227][228] Sokam tɛha ni Musulunsi adiini[229] daa tooi zooi la "Liberal Muslims" ban daa mo di bɛ zaŋ adiini kaya ni taɣada dolisi gɔmnanti tali,[230][231] so'chibi shɛli niriba shɛba ni daa bi saɣitishɛli.[232][233] [234] [235]

Demographics

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Zaŋ kana yuuni 2020, kamani vaabu 24% duniaa daadabiɛlim kalibu puuni, bee kamani niriba 1.9 billion, n-daa nyɛ Musulinima.[237][3][238][239][240][241] Yuuni 1900, lala buɣisibu ŋɔ daa nyɛla vaabu 12.3%,[242] yuuni 1990 di daa nyɛla vaabu 19.9%[204] ka bɛ daa buɣisi ni tooni ha di ni tooi paai vaabu 29.7% zaŋ chaŋ yuuni 2050.[243] Pew Research Center daa buɣisiya ni musulinima vaabu 87–90% n-nyɛ Sunni ka vaabu 10–13% nyɛ Shia.[244] Kamani 49 countries nyɛla Musulinima galisim,[245][246][247][248][249][250] ka vaabu 62% dunia Musulinima be Asia, ka 683 million be Indonesia,[251] Pakistan, India, ni Bangladesh ko.[252][253][254]Arab Musulinima n-nyɛ ban galisi pam dunia,[255] ka ban paya nyɛ Bengalis[256][257] ni Punjabis.[258] Buɣisibu nima pam wuhiya ni China mali kamani Musulinima 20 zaŋ chaŋ 30 million (1.5% zaŋ chaŋ 2% bɛ daadam biɛlim puuni).[259][260] Europe Musulinsi n-nyɛ adiini din galisi pahi buyi Dolodolo nuu yi yi tiŋgbana pam ni, ka daa zooi pam yuuni 2005,[261] ka pahi vaabu 4.9% Europe daadamnima ni yuuni 2016.[262]

Ban dolisiri kpɛri Musulinsi adiini ni dii bi pahiri adiini ŋɔ ni, dama baŋdiba buɣisiya ni ban kperi dini mini ban yiri nyɛla yim."[263] Amaa di ni tooi niŋ ka niriba 3 million yi bɛ adiini nima ni n-kpe Musulinsi adiini ni zaŋ chaŋ yuuni 2010 ni 2050, ka di pam yɛn nyɛla Sub Saharan Africa (2.9 million).[264][265]Lahabali din yina CNN nima sani wuhiya ni, "Musulinsi adiini nyɛla niriba yaɣayaɣa ni kperi shɛli ni, ban yi polo pam n-nyɛ "African-Americans".[266] Britain tiŋgbani ni, kamani niriba tusaa ayɔbu n-kperi Musulinsi adiini ni yuuni kam, lahabali din yina British Muslims Monthly Survey ni wuhi shɛm, Ban daa kperi Musulinsi adiini pam Britain tiŋgbani ni daa nyɛla paɣaba.[267] "The Huffington Post" ni wuhi shɛm, "Ni ban ti li zaɣa wuhiya ni niriba 20,000 America n-dolisiri kperi Musulinsi adiini ni yuuni kam", ka bɛ pam nyɛ paɣaba mini African-Americans.[268][269]

Di kalinli ni, Musulinsi adiini n-nyɛ adiini din zoori yomyom, ka ni tooi niŋ adiini din galisi pɔi ka 21st century naan yi naai, n-gari Dolodolo adiini.[270][271] Di buɣisiya ni, zaŋ chaŋ yuuni 2050, ni Musulinima kalinli ni tooi miri Dolodolonima ban be dunia, "ka di nyɛla Musunima ni dɔɣiri shɛm zuɣu."[271]

Main branches or denominations

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Sunni

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Sunni Musulinsi, bee Sunnism, n-nyɛ Musulinsin adiini pubu yaɣili din galisi pam.[272][273][274] Lala bachi ŋɔ nyɛla bachi din nyɛ "ahl as-sunna wa'l-jamaat" zaɣ'ŋmaa,ka di gbunni nyɛ "sunna niriba (Muhammad tuuntumsa) ni mabiligu".[275] Sunni Musulinsi adiini nyɛla bɛ ni booni shɛli saha shɛŋa "orthodox Islam",[276][277][278] amaa baŋdiba shɛba bi saɣiti li, ka ban pa Sunni nima pam ni tooi nyɛ ka di nyɛ taali.[279] Sunni nima, bee saha shɛŋa "Sunnites", ni tuuli "caliphs" niriba anahi n-daa nyɛ ban zani Muhammad zaai ka zaŋ di shɛhira dalim hadiisi nima dibaa ayɔbu, ka doli di puuni yini: Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki bee Shafi'i.[280][281]

Shia

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Shia Islam, bee Shi'ism, n-nyɛ Musulinsi adiini din galisin pahi buyi Musulinsi adiini pubu ni.[282][283][244] Shias, bee Shiites, za mi ni Muhammad fa'diriba ban nyɛ toondaannima nyƐla ban yina Muhammad daŋ ni bɛ ni boli shɛba Ahl al-Bayt ni lala kpamba, bɛ ni boli shɛba "Imams", nyɛla ban mali tabiibi.[284][285] Shias nyɛla ban doli Ja'fari school of jurisprudence.[286]

Muhakkima

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Ban doli Ibadi Islam bee Ibadism paai kamani Musulinima 1.45 million dunia yaɣa zaa (~0.08% Musulinima), ka bɛ pam be Oman.[287] Ibadism nyɛla bɛ ni lihi shɛili ka di nyɛ kharijites balishɛli, amaa Ibadis maŋmaŋa bɛ saɣiti lala yɛltɔɣa ŋɔ. Kharijites daa nyɛla ninvuɣi shɛba ban ni gaaba ni Caliph Ali ni o ni daa saɣiti ninvuɣi so bɛ ni daa dihitabili ni o tumdila taya ni bɛ bɔ maligu taba sunsuuni.Kamani kharijite pubu pa, Ibadism bɛ kali ninvuɣ'shɛba ban tumdi taya pahi ban bi ti yarida ni. Ibadi hadiisi, kamaniJami Sahih lahabali, malila ban daa daŋna ha yɛltɔɣa n-tumdi tuma, amaa Ibadi hadiisinima pam gba nyɛla din be Sunni lahabaya din zani di naba zuɣu ni ka Ibadis tooi saɣiritiri lala Sunni lahabaya ŋɔ.[288]

Other denominations

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]- "Ahmadiyya Movement" daa kpala British India yuuni 1889 ka ŋun daa kpali nyɛ Mirza Ghulam Ahmad ŋun yina Qadian, ŋun daa yɛli ni o nyɛla Messiah so yɛla bɛ ni yɛli ("Christ buyi labbu na ni"), Musulinima daa gulila Mahdi n-ti tabili "subordinate" prophet zaŋ ti Musulinsi adiini toondana Muhammad (S.W.A).[289][290] Dihitabili balibbu beni ni Ahmadis wuhibu zaŋ maɣisi Musulinsi adiininima din pahi,[289][291][292][290] n-ti tabili kahigibu ni Quranic yɛltɔga kpani Khatam an-Nabiyyin[293] ni Anabi yisa labbu na din pahiri buyi ("Messiah's Second Coming").[291][294] Musulinima shɛba nyɛla ban zaɣisi li[295] ni Ahmadis shɛba kubu tiŋgbani shɛŋa ni,[291] di bahi bahindi Pakistan,[291][296] luɣ'shɛli Pakistan gɔ~mnanti ni yɛli ni bɛ pala Musulinima.[297] Ban doli Ahmadiyya Movement Musulinsi adiini puuni pula buyi: Tuuli dini n-nyɛ "Ahmadiyya Muslim Community", din na galisi saha ŋɔ ni, ni Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement for the Propagation of Islam.[291]

- "Alevism" nyɛla "syncretic" ni "heterodox" Musulinsi adiini kali, ban doli (bāṭenī) baŋsibu zaŋ chaŋ Ali mini Haji Bektash Veli.[298] Alevism nyɛla 14th century Turkish ni dihi shɛli tabili taba laɣimbu.[299] Buɣisibu buɣisiya ni 10 million zaŋ chaŋ 20 million (~0.5–1% Musulinima zaa puuni) n-nyɛ Alevis duniya zaa.[300]

- Quranism nyɛla Musulinsi adiini laɣingu yaɣ'shɛli ka di wuhiri ni Musulinsi adiini zalisi mini di baŋsibu tu ni di tam Quran zuɣu ka di pa ni sunnah bee Hadith,[301] ni Alikuraani baŋdiba baŋsibu zaŋ chaŋ Musulinsi adiini daantalisi anu la ni.[302] Lala laɣingu ŋɔ pili la 19th century zaŋ kana, ni ban tɛhiri kamani Syed Ahmad Khan, Abdullah Chakralawi ni Ghulam Ahmed Perwez ŋun be India m-bɔhiri hadiisi pilli.[303] Egypt tiŋgbani ni, Muhammad Tawfiq Sidqi sabila lahabali din nyɛ "Islam is the Quran alone" Al-Manār lahabali ni, ka ŋme nangbankpeeni ni Quran konko zaŋ tumtuma.[304] 20th century bahigu Quran baŋda Rashad Khalifa, Egyptian-American baŋdi ŋun yɛli ni o daa yimina ni "numerological code in the Quran", ka kpa Quran baŋdiba laɣingu United Submitters International.[305]

Law and jurisprudence

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Sharia n-nyɛ adiini zaligu din pahi nam Musulunsi kaya ni taɣa.[306][307] Di yimina Musulunsi adiini puuni, di bahi bahindi Quran mini Hadith. Larigu ni, bachi din nyɛ sharīʿah zanimi ti Naawuni ni bɔri zali shɛli ka di gabiri ni fiqh, din zani ti di baŋsibu tɔnyɛligi.[308][309] Bɛ ni mali li tumdi tuma ʒaamani ŋɔ nyɛla din tahiri nangbankpeeni na nadaa Musulinima mini ban niŋdi taɣibunima.[306]

Nadaaha lahabali din jendi zalisi gbubila sharia ni yi luɣ'shɛŋa na yaɣa dibaa anahi: dini n-nyɛ Quran, sunnah (Hadith ni Sira), qiyas, n-ti pahi ijma.[310] Shikuruti pam kpuɣila sochibisi balibu ni di yihi sharia zalisi kundunima ni ka di nyɛla bɛ yɛn dolila so shɛli bɛ ni boli ijtihad.[308] Nadaa zalisi gbubila yaɣa dibaa ayi,ʿibādāt (rituals) mini muʿāmalāt (social relations), ka di laɣim taba gbubi yaɣa pam.[308] Di tuma chaŋmi ti gbaai pubu dibaa anu la puuni yini, ahkam: "mandatory" (fard), "recommended" (mustahabb), "permitted" (mubah), "abhorred" (makruh), "prohibited" (haram).[308][309] Champaŋ nyɛla Musulinsi ni kpaŋsi shɛli[311] ka tibidarigibo niŋ talahi ti taali tumdiba ni bɛ ni tum taali maa shɛm tariga.[312] Sharia shɛŋa chanimi kperi "Western notion of law" ni ka di shɛŋa mi chanmi doli Naawuni ni bɔri shɛli biɛhigu ni.[309]

Schools of jurisprudence

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Society

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Daily and family life

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Dakulo pam tuma chaŋmi n-ti lu n-zahim adab, bee "etiquette". Bindiri shɛŋa din chihiri n-nyɛ kurichu nimdi, ʒim mini binkpiŋ nimdi. Alaafee nyɛla bɛ ni nyɛ ka shɛli nyɛ dihitabili din yina Naawuni sani, kamani daam binnyura nyɛla din chihira.[314] Nimdi kam tum ni di yina nimadi din dibu bi chihiri ni ka bɛ lahi kɔrigili ni Naawuni yuli, Jew, be Doldolo, gbaai yihi tɔhigu dini bee zahim din gbahi kuliga ni.[315][316][317] Kɔbiri nyɛla bɛ ni kpaŋsiri shɛli dobba ni[318] ni ningbuna malibu, kamani dalima din ka nyahibu sabi pa ningbuna zuɣunyɛla bɛ ni mɔŋ shɛli.[lower-alpha 3][320] "Silk" mini salima nyɛla bɛ ni mɔŋ Musulinsi adiini dobba ni bɛ zaŋ niŋ bɛ maŋa.[321] Haya, ka bɛ tooi lɛbigiri di gbunni "vi" bee "gahimbu", nyɛla bɛ ni kpaŋsi ni Musulimi mali shɛli[322] ka wuhiri Musulimi biɛɣu kulo kam biɛhigu. Kamani shɛhira, nema yɛbu Musulinsi adiini ni tumi ni di gahim, din nima n-nyɛ "hijab" zaŋ ti paɣaba. Lala n-lahi nyɛli, ninsalisili sabita gba nyɛla bɛ ni kpaŋsi shɛli.[323] Yɛlimaŋ'tibo ni adiininima din pahi (tasamuh) nyɛla Sunni Musulinsi mabiligu ni saɣiti shɛli.[324][325][326]

Musulinsi amiliya niŋbu ni, doo maa tumi ni o yo asadaachi (mahr).[327][328][329] Musulinima pam mali paɣa yini yini.[330][331] Musulim dobaa ni tooi mali paɣa bɔbigu kani doo bɔ paɣa paai anahi. Musulinsi kpaŋsiya ni doo yi ku tooi tum adalich o paɣaba sunsuuni, ni din ŋuna ŋun bɔm paɣa yini. Di daliri shɛli nyɛla ni doo yi bo paɣaba pam o ni tooi sɔŋ ban ku tooi nyaŋ kamani liɣiri polo (e.g. pakoya). Amaa, paɣa tuuli mini o yidana ni tooi gbaai ni o bi lahi yɛn bo paɣa pahi.[332][333] Amiliya niŋbu lahi mali balibu zaŋ chaŋ taɣada nima ni.[334] Musulinsi adiini bi saɣiti ni paɣa mali yidaannima pam.[335]

Bɛ yi dɔɣi bia naai, bɛ moonil la jiŋli n-niŋ o nudirigu ni ka yiɣisi jiŋli n-niŋ o nuzaa ni.[336] Dabaa ayopɔin dali, ka bɛ niŋ suuna, ka bɛ kɔrigi binkɔbigu ka piri o nimdi tari ban bi nyanda.[337] Bɛ pindila bia maa zuɣ, ka bɔ zabiri maa liɣiri ti ban ka yi ko.[337] Do gunibu, bɛ ni boli shɛli khitan,[338] nyɛla Musulinima ni niŋdi shɛli.[339][340] Daadam laamba jilima tibu, ka lahi yuuniba viɛnyɛla nyɛa jama.[341]

Bɛ kpaŋsiya ni Musulimi yi yɛn kpi ka o yɛli Shahada o yɛltɔga bahigu.[342] Ku'yiya chandi nyɛla bɛ ni tibigi shɛli. Kpim sɔɣibu Musulinsi adiini ni, di ku tu ni nira yi kuli kpi ka bɛ sɔɣi o yomyom, ka hawa pishi ni anahi zuɣu ni. Bɛ surila kum maa kom, gbaa yihi "martyrs", paɣa surila paɣaba ka dobba suri dobba, ka bɛ niŋ o situra yuli booni kafan.[343] Kum jiŋli yuli booni Salat al-Janazah nyɛla bɛ ni puhiri shɛli. Pampam kuhibu bi saɣiti. Bɛ dii bi kpaŋsi kum adakanima ka bi lahi dalindi gbala, hali nanima gba.[344]

Arts and culture

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]- 14th century Great Mosque of Xi'an in China

- 16th century Menara Kudus Mosque in Indonesia showing Indian influence

Malaika nima

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Malaika nima (Arabic: ملك, malak) nyɛla binnamda shɛŋa yɛltɔɣa bɛ ni yɛlli Alquran [20] mini hadiisi ni.[21] Bɛ nyɛla bɛ buɣirisi shɛba Naawuni ni nam ni bɛ Jam o ka lahi tumdi tun'shɛŋa kamani yɛligu din yina Naawuni sani, sabiri ninsali kam tuma ka deeri ninsali kam nyɛvuli o kpibu saha. Bɛ nyɛla bɛ ni buɣisi ni bɛ zaŋ la neeisim nam ba (nūr)[345][346][347] bee buɣum (nār).[348][349][350][351] Musulinsi adiini malaika nima tooi zooi ka bɛ nyɛla anthropomorphic forms ka laɣim ni supernatural anfooni nima kamani kpiŋkpana, nyɛ ban galisi.[29][352][353][354] Nahingbana din niŋ bayana zaŋ n-ti malaika nima nyɛ bɛ ka niŋgbana yɛlibora mini suhiyurilim kamani dibu mini nyubu.[33] Bɛ shɛba kamani Gabriel (Jibrīl) mini Michael (Mika'il) nyɛla Alquran ni boli shɛba yuya. Malaika nima nyɛla ban tuma galisi "literature" zaŋ jandi Mi'raj, ni ka Muhammad daa nya malaika nima pam o chani alizanda ni.[21]

Mysticism

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Sufism (Arabic: تصوف, tasawwuf),nyɛla "mystical-ascetic" sodoligu zaŋ chaŋ Musulinsi adiini din bɔri Nawwuni miribu ka doli Naawuni ni adalichi.[355][356][357] Sufi baŋdiba kahigi tasawwuf ka di nyɛla "n-niŋ suhu kasi ka mɔŋ binshɛɣu kam dolibu ka doli Naawuni ko", Qur'an karimbu ni sunnah dolibu mini fiqh zaŋ tum tuma ninsali biɛhigu ni.[358][359][360][361][362] Ahmad ibn Ajiba kahigi tasawwuf ka di nyɛla "kali ni labbu, ka di piligu nyɛ baŋsim, di sunsuuni n-nyɛ zaŋ ku bukaata [lala baŋsim maa nyaaŋa], ka di bahigu nyɛ pini [din yina Naawuni sani]."[363]Di pala musulinsi adiini pubu yaɣ'shɛli, ka ban be din ni be Musulinsi adiini pubu yaɣ'shɛŋa. Isma'ilism, ban baŋsibu yirina Gnosticism mini Neoplatonism ni[364] n-ti tabili "Illuminationist" mini "Isfahan"Musulinsi adiini baŋsim shikuru, nyɛla din yina ni Musulinsi adiini kahigibu.[365] Hasan al-Basri, tuuli Sufi nyɛla bɛ ni tooi kani so pahiri tuuli tuuli ha Sufinima ni,[366] ka di yaa jendi dabiɛm zaŋ chaŋ tum birigi Naawuni ni bɔri shɛm ni. Zaŋ maɣisi ni, Sufinima ban daa doli nyaaŋa na ka mali yuya, kamani Mansur Al-Hallaj mini Jalaluddin Rumi, daa lihila adiini ni yurilim zaŋ ti Naawuni.[367][368]

Prayer

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

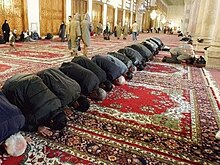

Suhigu musulinsi puuni ka bɛ booni as-salah bee aṣ-ṣalāt (Arabic: الصلاة), di nyɛla soli shɛli bɛ ni doli diri Naawuni fiila ka nyɛ din mali binshɛli ka bɛ kuli niŋdi labiri niŋda ka booni li rakat di ni nyɛ bowing mini prostrating zaŋ n-ti Naawuni. Dabisili kam puuni bɛ suhiri la Naawuni bunu. Suhigu ŋɔ nyɛla bɛ ni niŋdi shɛli Larigu balli ni ka nyɛ ban tuhiri Kaaba. Di nyɛla din lahi bori kashi tali niŋbu di ni nyɛ wudu ritual wash bee talahi tali ni ghusl niŋgbana zaa paɣibu.[369][370][371][372]

Jiŋli ni nyɛla place of worship zaŋ n-ti musulinnima ka bɛ tooi booni Larigu balli puuni masjid. Jiŋli tuma nyɛla luɣ'shɛli musulininma ni laɣindi taba suhiri Naawuni amaa di lahi nyɛla laɣingu shɛŋa din kpa talahi shee zaŋ n-ti Muslim community. Kamani ŋmahinli, Masjid an-Nabawi ("Prophetic Mosque") din be Medina, Saudi Arabia,nyɛla biɛhigu shee zaŋ n-ti fakari ni mali shɛba.[373] Minarets nyɛla ban yunsiri boligu shɛli bɛ ni boli adhan, boligu din wuhiri suhibu saha.[374][375]

Almsgiving

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Zakat (Arabic: زكاة, zakāh), di ni tooi lahi sabi Zakāt bee Zakah, nyɛla Naawuni zuɣu tibu balli shɛli ka nyɛ din mali di ni tiri shɛm tariga (yuuni puuni kɔbigi puuni vaabu 2.5% )[376] zaŋ n-ti accumulated wealth n-ti ninvuɣ shɛba ban ni tooi niŋ li sɔŋ fara ni mali ninvuɣ shɛba kamani samli ni mali ninvuɣ shɛba, ŋun doli soli, n-ti pahi ninvuɣ shɛba zaa ban to zakat deebu. Di nyɛla binshɛli din nyɛ welfare n-ti musulinsi ʒilɛni.[377] Di nyɛla adiini maa daatali yini ni bɛ sɔŋmi ban ka bee ban to zakat ŋɔ deebu dama lala buni shɛŋa zaa bɛ ni mali maa nyɛla Naawuni dini ,[378] ka lahi nyɛ din niŋdi niri buni kashi.[379] [380] Sadaqah, din ŋmani Zakat nyɛla bɛ ni kpaŋsiri niriba ka di leei nyɛ suhiyubu Naawuni zuɣu tibu.[381][382] Waqf gba nyɛla charitable trust ka bɛ leei mali sɔŋdi ashibiti nima mini shikuruti nima ni musulim nima ʒilɛni .[383]

Pilgrimage

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

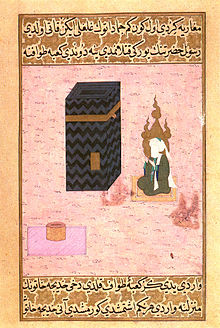

Musulinsi adiini pilgrimage,bɛ booni li la "ḥajj" (Arabic: حج), di nyɛla binshɛli musulimi nima ni niŋdi kamani yim niri nyɛvuli puuni di yi niŋ ka a mali di yiko Islamic month zaŋ n-ti Dhu al-Hijjah. Lala Hajj ŋɔ lahabaya tooi nyɛla din jandi Abraham daŋ. Mecca, Hajj niŋdiba nyɛla ban chani gindi Kaaba buyopɔin zuɣu ka musulim nima mali dihitabili ni Abraham n-daa miɛ li jama shee, ka chani gindi Mount Safa and Marwa buyopɔin zuɣu, labiri kaani Abraham's paɣa Hagar chandi, ŋun daa lihiri m-bori kom shee ni o ti o bia yuli booni Ishmael kurumbuna ni ha pɔi ka Mecca lɛbigi tiŋa.[384][385][386] Aʒi ŋɔ gba nyɛla dabisili bɛ ni suhiri ka jamdi Mount Arafat ka di nahingbaŋ nyɛ stoning the Devil.[387] Musulimi nima ban nyɛ dabba zaa nyɛla ban yɛri neen'piɛlli ayi ka bɛ boli ihram.[388][389] Aʒi ŋɔ biɛhi shɛli nyɛ, Umrah, di pa talahi ka nyɛ di ni tooi niŋ saha kam yuuni puuni. Aʒi ŋɔ binshɛŋa nyɛla din niŋdi Medina,ni ka Muhammad daa kpi n-ti pahi Jerusalem, tiŋa zaŋ Al-Aqsa.[390][391]

Other acts of worship

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

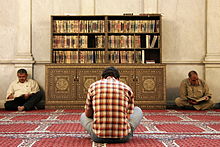

Musulimi nima nyɛla ban karindi ka gbaari Alquran zaa bee di yaɣa shɛŋa. Tajwid nyɛ zalikpana zaŋ n-ti Alquran viɛnyɛla bolibu .[392] Musulimi nima pam nyɛla ban karindi Alquran noliri goli ni.[393] Bɛ booni la ninvuɣ so ŋun gbaai Alquran zaa niŋ o zuɣu hafiz ("memorizer"), ka hadiisi yɛli ni lala niriba ŋɔ nyɛla ban sani tooi suhi deei shɛba Judgment Day.[394]

Adua suhi ti Naawuni, Larigu balli ni Arabic duʿāʾ (Arabic: دعاء ar) nyɛla din mali di zalikpana kamani raising hands kamani nuhi wuhibu.[395]

Arkan al-Islam (five pillars of Islam):[1]

Influences on other religions

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Laɣinsi shɛŋa, kamani Druze,[396][397][398] Berghouata ni Ha-Mim, nyɛla din yina Musulinsi ni bee ka di mini Musulinsi adiini mali dihitabili yinsi, amaa di zaa nyɛla adiini yini bee di yila Musulinsi adiini ni na nyɛla nangbankpeeni ni be shɛli.[399] Druze lahi nyɛla din chaŋ pirigiIsma'ilism pirim la di ni mali di maŋ zalisi la, ka naan yi waligi ka che Ismāʿīlīsm mini Islam zaa; di shɛŋa n-nyɛ dihitabili din nyɛ ni Imam Al-Ḥākim bi-Amr Allāh daa nyɛla Naawuni taɣimalisi.[400][401] Yazdânism nyɛla din laɣim Kurdish dihitabili mini Islamic Sufi soya din kpeKurdistan ni , Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir ni daa ʒi shɛli na 12th century.[402] Bábism yimina Twelver Shia ni ka yina Siyyid 'Ali Muhammad i-Shirazi al-Bab sani ka o nyaandoliba puuni yino Mirza Husayn 'Ali Nuri Baha'u'llah kpa Baháʼí Faith.[403] Sikhism, Guru Nanak ni kpa shɛli 15th century bahigu Punjab, ka di kperi ni Hinduism, ni Musulinsi adiini yaɣ'shɛŋa.[404]

Citations

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]- 1 2 Naden, Tony. 2014. Dagbani dictionary. Webonary.

- ↑ English pronunciation of Islam.

- 1 2 Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project - Research and data from Pew Research Center (21 December 2022).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schimmel, Annemarie. "Islam". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ Definition of Islam | Dictionary.com (en).

- ↑ Haywood, John (2002). Historical Atlas of the Medieval World (AD 600 - 1492) (in English) (1st ed.). Spain: Barnes & Noble, Inc. p. 3.13. ISBN 0-7607-1975-6.

- ↑ "Siin Archived 7 Silimin gɔli September 2011 at the Wayback Machine." Lane's Lexicon 4. – via StudyQuran.

- ↑ Lewis, Barnard; Churchill, Buntzie Ellis (2009). Islam: The Religion and The People. Wharton School Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-13-223085-8.

- ↑ "Muslim." Lexico. UK: Oxford University Press. 2020.

- ↑ Esposito (2000), pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Mahmutćehajić, Rusmir (2006). The mosque: the heart of submission. Fordham University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8232-2584-2.

- ↑ Gibb, Sir Hamilton (1969). Mohammedanism: an historical survey. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780195002454.

Modern Muslims dislike the terms Mohammedan and Mohammedanism, which seem to them to carry the implication of worship of Mohammed, as Christian and Christianity imply the worship of Christ.

- ↑ Beversluis, Joel, ed. (2011). Sourcebook of the World's Religions: An Interfaith Guide to Religion and Spirituality. New World Library. pp. 68–9. ISBN 9781577313328. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ↑ "Tawhid". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_7454

- ↑ Ali, Kecia; Leaman, Oliver (2008). Islam : the key concepts. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-39638-7. OCLC 123136939.

- ↑ Campo (2009), p. 34, "Allah".

- ↑ Leeming, David. 2005. The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-15669-0. p. 209.

- ↑ God. PBS.

- 1 2 Burge (2015), p. 23.

- 1 2 3 4 Burge (2015), p. 79.

- ↑ "Nūr Archived 23 Silimin gɔli April 2022 at the Wayback Machine." The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0874

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQSIM_00261

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc. – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0846

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQSIM_00156

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- 1 2 Burge (2015), pp. 97–99.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvcdoi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0642

- 1 2 Çakmak (2017), p. 140.

- ↑ Burge (2015), p. 22.

- 1 2 Tɛmplet:HarvcA chirim ya: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "610CE" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Watt, William Montgomery (2003). Islam and the Integration of Society. Psychology Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-415-17587-6. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ↑ Esposito (2004), pp. 17–18, 21.

- ↑ (1987) "The Cantillation of the Qur'an". Asian Music (Autumn – Winter 1987): 3–4.

- 1 2 Ringgren, Helmer. "Qurʾān". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2021. "The word Quran was invented and first used in the Quran itself. There are two different theories about this term and its formation."

- ↑ "Tafsīr". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ Esposito (2004), pp. 79–81.

- ↑ Jones, Alan (1994). The Koran. London: Charles E. Tuttle Company. p. 1. ISBN 1842126091.

Its outstanding literary merit should also be noted: it is by far, the finest work of Arabic prose in existence.

- ↑ Arberry, Arthur (1956). The Koran Interpreted. London: Allen & Unwin. p. 191. ISBN 0684825074.

It may be affirmed that within the literature of the Arabs, wide and fecund as it is both in poetry and in elevated prose, there is nothing to compare with it.

- ↑ Kadi, Wadad, and Mustansir Mir. "Literature and the Quran." In Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an 3. pp. 213, 216.

- 1 2 Tɛmplet:HarvpA chirim ya: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "harvp|Esposito|2002b|pp=4–5" defined multiple times with different content - 1 2 Tɛmplet:HarvpA chirim ya: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "harvp|Peters|2003|p=9" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Bennett (2010), p. 101.

- ↑ BnF. Département des Manuscrits. Supplément turc 190. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Reeves, J. C. (2004). Bible and Qurʼān: Essays in scriptural intertextuality. Leiden: Brill. p. 177. ISBN 90-04-12726-7. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ Esposito, John L. 2009. "Islam." In Tɛmplet:Doi-inline, edited by J. L. Esposito. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530513-5. (See also: quick reference Archived 10 Silimin gɔli January 2021 at the Wayback Machine.) "Profession of Faith...affirms Islam's absolute monotheism and acceptance of Muḥammad as the messenger of Allah, the last and final prophet."

- ↑ Peters, F. E. 2009. "Allāh." In Tɛmplet:Doi-inline, edited by J. L. Esposito. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530513-5. (See also: quick reference Archived 26 Silimin gɔli September 2020 at the Wayback Machine.) "[T]he Muslims' understanding of Allāh is based...on the Qurʿān's public witness. Allāh is Unique, the Creator, Sovereign, and Judge of mankind. It is Allāh who directs the universe through his direct action on nature and who has guided human history through his prophets, Abraham, with whom he made his covenant, Moses/Moosa, Jesus/Eesa, and Muḥammad, through all of whom he founded his chosen communities, the 'Peoples of the Book.'"

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc

- ↑ Goldman, Elizabeth (1995). Believers: Spiritual Leaders of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-19-508240-1.

- ↑ al-Rahman, Aisha Abd, ed. 1990. Muqaddimah Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ. Cairo: Dar al-Ma'arif, 1990. pp. 160–69

- ↑ Awliya'i, Mustafa. "The Four Books Archived 12 Silimin gɔli September 2017 at the Wayback Machine." In Outlines of the Development of the Science of Hadith 1, translated by A. Q. Qara'i. – via Al-Islam.org. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ↑ Rizvi, Sayyid Sa'eed Akhtar. "The Hadith §The Four Books (Al-Kutubu'l-Arb'ah) Archived 12 Silimin gɔli September 2017 at the Wayback Machine." Ch 4 in The Qur'an and Hadith. Tanzania: Bilal Muslim Mission. – via Al-Islam.org. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_DUM_0467: "Ibn Sīnā, Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Sīnā is known in the West as 'Avicenna'."

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc

- ↑ Eschatology. The Oxford Dictionary of Islam.

- ↑ Esposito (2011), p. 130.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp; Encyclopedia of Islam and Muslim World, p. 565

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc

- ↑ "Paradise". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Andras Rajki's A. E. D. (Arabic Etymological Dictionary) (2002).

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp: "The idea of predestination is reinforced by the frequent mention of events 'being written' or 'being in a book' before they happen": Say: "Nothing will happen to us except what Allah has decreed for us..."

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc: The verb qadara literally means "to measure, to determine". Here it is used to mean that "God measures and orders his creation".

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0407

- ↑ Muslim beliefs – Al-Qadr. Bitesize – GCSE – Edexcel. BBC.

- ↑ Esposito (2010), p. 6.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc

- ↑ "Muhammad". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Ottomans : religious painting.

- ↑ Rabah, Bilal B. Encyclopedia of Islam.

- ↑ Ünal, Ali (2006). The Qurʼan with Annotated Interpretation in Modern English. Tughra Books. pp. 1323–. ISBN 978-1-59784-000-2. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Serjeant (1978), p. 4.

- ↑ Peter Crawford (2013-07-16), The War of the Three Gods: Romans, Persians and the Rise of Islam, Pen & Sword Books Limited, p. 83, ISBN 9781473828650, archived from the original on 28 December 2023, retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvc

- ↑ Melchert, Christopher (2020). "The Rightly Guided Caliphs: The Range of Views Preserved in Ḥadīth". In al-Sarhan, Saud (ed.). Political Quietism in Islam: Sunni and Shi'i Practice and Thought. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-1-83860-765-4. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ↑ Esposito (2010), p. 40.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Esposito (2010), p. 38.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- 1 2 Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ J. Kuiper, Matthew (2021). Da'wa: A Global History of Islamic Missionary Thought and Practice. Edinburgh University Press. p. 85. ISBN 9781351510721.

- ↑ Lapidus, Ira M. (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9.

- ↑ Holt & Lewis (1977), pp. 67–72.

- ↑ Harney, John (3 January 2016). "How Do Sunni and Shia Islam Differ?". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/04/world/middleeast/q-and-a-how-do-sunni-and-shia-islam-differ.html.

- ↑ Waines (2003), p. 46.

- ↑ Ismāʻīl ibn ʻUmar Ibn Kathīr (2012), p. 505.

- ↑ Umar Ibn Abdul Aziz By Imam Abu Muhammad Abdullah ibn Abdul Hakam died 214 AH 829 C.E. Publisher Zam Zam Publishers Karachi, pp. 54–59

- ↑ Noel James Coulson (1964). History of Islamic Law. King Abdulaziz Public Library. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-7486-0514-9. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ Houtsma, M.T.; Wensinck, A.J.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Gibb, H.A.R.; Heffening, W., eds. (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. Volume V: L—Moriscos (reprint ed.). Brill Publishers. pp. 207–. ISBN 978-90-04-09791-9. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ↑ Moshe Sharon, ed. (1986). Studies in Islamic History and Civilization: In Honour of Professor David Ayalon. BRILL. p. 264. ISBN 9789652640147. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ Mamouri, Ali (8 January 2015). "Who are the Kharijites and what do they have to do with IS?". Al-monitor. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2015/01/islamic-state-kjarijites-continuation.html.

- ↑ Blankinship (2008), p. 43.

- 1 2 3 Esposito (2010), p. 87.

- ↑ Puchala, Donald (2003). Theory and History in International Relations. Routledge. p. 137.

- ↑ Esposito (2010), p. 45.

- ↑ Al-Biladhuri, Ahmad Ibn Jabir; Hitti, Philip (1969). Kitab Futuhu'l-Buldan. AMS Press. p. 219.

- ↑ Lapidus (2002), p. 56.

- ↑ Lewis (1993), pp. 71–83.

- ↑ Lapidus (2002), p. 86.

- ↑ A chirim ya: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedEB-Sufism - ↑ Lapidus (2002), pp. 90, 91.

- ↑ Blankinship (2008), pp. 38-39.

- ↑ Omar Hamdan Studien zur Kanonisierung des Korantextes: al-Ḥasan al-Baṣrīs Beiträge zur Geschichte des Korans Otto Harrassowitz Verlag 2006 ISBN 978-3447053495 pp. 291–292 (German)

- ↑ Blankinship (2008), p. 50.

- ↑ Esposito (2010), p. 88.

- ↑ Doi, Abdur Rahman (1984). Shariah: The Islamic Law. London: Ta-Ha Publishers. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-907461-38-8.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ King, David A. (1983). "The Astronomy of the Mamluks". Isis 74 (4): 531–55. DOI:10.1086/353360. ISSN 0021-1753.

- ↑ Hassan, Ahmad Y. 1996. "Factors Behind the Decline of Islamic Science After the Sixteenth Century." Pp. 351–99 in Islam and the Challenge of Modernity, edited by S. S. Al-Attas. Kuala Lumpur: International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- ↑ Contributions of Islamic scholars to the scientific enterprise.

- ↑ The greatest scientific advances from the Muslim world (February 2010).

- ↑ Jacquart, Danielle (2008). "Islamic Pharmacology in the Middle Ages: Theories and Substances". European Review (Cambridge University Press) 16: 219–227.

- ↑ David W. Tschanz, MSPH, PhD (August 2003). "Arab Roots of European Medicine", Heart Views 4 (2).

- ↑ Abu Bakr Mohammad Ibn Zakariya al-Razi (Rhazes) (c. 865-925). sciencemuseum.org.uk.

- ↑ Alatas, Syed Farid (2006). "From Jami'ah to University: Multiculturalism and Christian–Muslim Dialogue". Current Sociology 54 (1): 112–132. DOI:10.1177/0011392106058837.

- ↑ Imamuddin, S.M. (1981). Muslim Spain 711–1492 AD. Brill Publishers. p. 169. ISBN 978-90-04-06131-6.

- ↑ Toomer, G. J. (Dec 1964). "Review Work: Matthias Schramm (1963) Ibn Al-Haythams Weg zur Physik". Isis 55 (4). “Schramm sums up [Ibn Al-Haytham's] achievement in the development of scientific method.”

- ↑ Al-Khalili, Jim (4 January 2009). "The 'first true scientist'". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7810846.stm.

- ↑ Gorini, Rosanna (October 2003). "Al-Haytham the man of experience. First steps in the science of vision". Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine 2 (4): 53–55.

- ↑ (May 2001) "On the prehistory of programmable machines: musical automata, looms, calculators". Mechanism and Machine Theory 36 (5): 589–603. DOI:10.1016/S0094-114X(01)00005-2.

- ↑ (18 September 2007) "Stages in the History of Algebra with Implications for Teaching". Educational Studies in Mathematics 66 (2): 185–201. DOI:10.1007/s10649-006-9023-7.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Young, Mark (1998). The Guinness Book of Records. Bantam. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-553-57895-9.

- 1 2 Brague, Rémi (2009). The Legend of the Middle Ages: Philosophical Explorations of Medieval Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. University of Chicago Press. p. 164. ISBN 9780226070803.

Neither were there any Muslims among the Ninth-Century translators. Amost all of them were Christians of various Eastern denominations: Jacobites, Melchites, and, above all, Nestorians... A few others were Sabians.

- ↑ Hill, Donald. Islamic Science and Engineering. 1993. Edinburgh Univ. Press. ISBN 0-7486-0455-3, p.4

- ↑ Rémi Brague, Assyrians contributions to the Islamic civilization Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Meri, Josef W. and Jere L. Bacharach. "Medieval Islamic Civilization". Vol. 1 Index A–K Archived 28 Silimin gɔli December 2023 at the Wayback Machine. 2006, p. 304.

- ↑ Saliba, George. 1994. A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-8023-7. pp. 245, 250, 256–57.

- ↑ Arnold (1896), pp. 125–258.

- ↑ The Spread of Islam.

- ↑ Ottoman Empire. Oxford Islamic Studies Online (6 May 2008).

- ↑ Adas, Michael, ed. (1993). Islamic and European Expansion. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 25.

- ↑ Metcalf, Barbara (2009). Islam in South Asia in Practice. Princeton University Press. p. 104.

- ↑ Peacock (2019), p. 20–22.

- ↑ Çakmak (2017), pp. 1425–1429.

- ↑ Farmer, Edward L., ed. (1995). Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. BRILL. p. 82. ISBN 9004103910. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- ↑ Israeli, Raphael (2002). Islam in China. p. 292. Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-0375-X.

- ↑ Dillon, Michael (1999). China's Muslim Hui Community. Curzon. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7007-1026-3.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ Subtelny, Maria Eva (November 1988). "Socioeconomic Bases of Cultural Patronage under the Later Timurids". International Journal of Middle East Studies 20 (4): 479–505. DOI:10.1017/S0020743800053861.

- ↑ Nasir al-Din al-Tusi. University of St Andrews (1999).

- ↑ Ghiyath al-Din Jamshid Mas'ud al-Kashi. University of St Andrews (1999).

- ↑ Drews, Robert (August 2011). "Chapter Thirty – "The Ottoman Empire, Judaism, and Eastern Europe to 1648"" (PDF). Coursebook: Judaism, Christianity and Islam, to the Beginnings of Modern Civilization. Vanderbilt University. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ↑ Peter B. Golden: An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples; In: Osman Karatay, Ankara 2002, p. 321

- ↑ Gilbert, Marc Jason (2017), South Asia in World History, Oxford University Press, p. 75, ISBN 978-0-19-066137-3, archived from the original on 22 September 2023, retrieved 15 January 2023

- ↑ Ga ́bor A ́goston, Bruce Alan Masters Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire Infobase Publishing 2010 ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7 p. 540

- ↑ Algar, Ayla Esen (1 January 1992). The Dervish Lodge: Architecture, Art, and Sufism in Ottoman Turkey. University of California Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-520-07060-8. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2020 – via Google Books.

- ↑ CONVERSION To Imami Shiʿism in India (English). Iranica Online.

- ↑ Tucker, Ernest (1994). "Nadir Shah and the Ja 'fari Madhhab Reconsidered". Iranian Studies 27 (1–4): 163–179. DOI:10.1080/00210869408701825.

- ↑ Tucker, Ernest (29 March 2006). "Nāder Shāh". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- 1 2 Mary Hawkesworth, Maurice Kogan Encyclopedia of Government and Politics: 2-volume set Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-1-136-91332-7 pp. 270–271

- ↑ Esposito (2010), p. 150.

- ↑ Richard Gauvain Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-0-7103-1356-0 p. 6

- ↑ Spevack, Aaron (2014). The Archetypal Sunni Scholar: Law, Theology, and Mysticism in the Synthesis of al-Bajuri. SUNY Press. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-1-4384-5371-2. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ↑ Donald Quataert The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922 Cambridge University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-521-83910-5 p. 50

- 1 2 Ga ́bor A ́goston, Bruce Alan Masters Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire Infobase Publishing 2010 ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7 p. 260

- 1 2 3 Musa, Shahajada Md (2022-08-23). The Emergence of a Scholar from a Garrison Society: A contextual analysis of Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhāb's doctrine in the light of the Qur'ān and Hadīth (masters thesis) (in English). University of Wales Trinity Saint David. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ↑ "Graves desecrated in Mizdah". Libya Herald. 4 September 2013. http://www.libyaherald.com/2013/09/04/graves-desecrated-in-mizdah/#axzz2jWG0vDDO.

- ↑ Esposito (2010), p. 146.

- ↑ Nicolas Laos The Metaphysics of World Order: A Synthesis of Philosophy, Theology, and Politics Wipf and Stock Publishers 2015 ISBN 978-1-4982-0102-5 p. 177

- ↑ Rubin, Barry M. (2000). Guide to Islamist Movements. M.E. Sharpe. p. 79. ISBN 0-7656-1747-1. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Esposito (2010), p. 147.

- ↑ Esposito (2010), p. 149.

- ↑ Robert L. Canfield (2002). Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 131–. ISBN 978-0-521-52291-5. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ↑ Sanyal, Usha (23 July 1998). "Generational Changes in the Leadership of the Ahl-e Sunnat Movement in North India during the twentieth Century". Modern Asian Studies 32 (3): 635–656. DOI:10.1017/S0026749X98003059.

- ↑ Lapidus (2002), pp. 358, 378–380, 624.

- ↑ Buzpinar, Ş. Tufan (March 2007). "Celal Nuri's Concepts of Westernization and Religion". Middle Eastern Studies 43 (2): 247–258. DOI:10.1080/00263200601114091.

- ↑ Lauziere, Henri (2016). The Making of Salafism: Islamic Reform in the Twentieth Century. New York, Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-0-231-17550-0.

Beginning with Louis Massignon in 1919, it is true that Westerners played a leading role in labeling Islamic modernists as Salafis, even though the term was a misnomer. At the time, European and American scholars felt the need for a useful conceptual box to place Muslim figures such as Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, Muhammad Abduh, and their epigones, all of whom seemed inclined toward a scripturalist understanding of Islam but proved open to rationalism and Western modernity. They chose to adopt salafiyya—a technical term of theology, which they mistook for a reformist slogan and wrongly associated with all kinds of modernist Muslim intellectuals.

- ↑ "Political Islam: A movement in motion". Economist Magazine. 3 January 2014. https://www.economist.com/blogs/erasmus/2014/01/political-islam.

- ↑ Smith, Wilfred Cantwell (1957). Islam in Modern History. Princeton University Press. p. 233. ISBN 0-691-03030-8.

- ↑ Mecelle. The Oxford Dictionary of Islam.

- ↑ "New Turkey". Al-Ahram Weekly (488). 29 June – 5 July 2000. http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2000/488/chrncls.htm.

- ↑ «مملكة الحجاز».. وقــصـــة الـغــزو المـســلّـــح (ar) (2020-05-05).

- ↑ Bani Issa, Mohammad Saleh (2023-11-01). "Factors of stability and sustainable development in Jordan in its first centenary 1921–2021 (an analytical descriptive study)". Heliyon 9 (11): e20993. DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20993. ISSN 2405-8440. PMID 37928029.

- 1 2 والخلفاء, قصص الخلافة الإسلامية (2023-03-31). قصص الخلافة الإسلامية والخلفاء (in English). Austin Macauley Publishers. ISBN 978-1-3984-9251-6. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ↑ Doran, Michael (1999). Pan-Arabism before Nasser: Egyptian power politics and the Palestine question. Studies in Middle Eastern history. New York Oxford: Oxford university press. ISBN 978-0-19-512361-6.

- ↑ Landau, Yaʿaqov M. (1994). The politics of Pan-Islam: ideology and organization ([Rev. and updated] paperback (with additions and corr.) ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-827709-5.

- ↑ "Organization of the Islamic Conference". BBC News. 26 December 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/country_profiles/1555062.stm.

- ↑ Haddad & Smith (2002), p. 271.

- ↑ Zabel, Darcy (2006). Arabs in the Americas: Interdisciplinary Essays on the Arab Diaspora. Austria: Peter Lang. p. 5. ISBN 9780820481111.

- 1 2 The Future of the Global Muslim Population (Report). Pew Research Center. 27 January 2011. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2017.A chirim ya: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Pew Research Center-2011" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Tɛmplet:Harvp

- ↑ "Are secular forces being squeezed out of Arab Spring?". BBC News. 9 August 2011. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-14447820.

- ↑ Slackman, Michael (23 December 2008). "Jordanian students rebel, embracing conservative Islam". New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/24/world/middleeast/24jordan.html.

- ↑ Kirkpatrick, David D. (3 December 2011). "Egypt's vote puts emphasis on split over religious rule". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/04/world/middleeast/egypts-vote-propels-islamic-law-into-spotlight.html.

- ↑ Lauziere, Henri (2016). The Making of Salafism: Islamic Reform in the Twentieth Century. New York, Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-231-17550-0.

Prior to the fall of the Ottoman Empire, leading reformers who happened to be Salafi in creed were surprisingly open-minded: although they adhered to neo-Hanbali theology. However, the aftermath of the First World War and the expansion of European colonialism paved the way for a series of shifts in thought and attitude. The experiences of Rida offer many examples... he turned against the Shi'is who dared, with reason, to express doubts about the Saudi-Wahhabi project... . Shi'is were not the only victims: Rida and his associates showed their readiness to turn against fellow Salafis who questioned some of the Wahhabis' religious interpretations.

- ↑ G. Rabil, Robert (2014). Salafism in Lebanon: From Apoliticism to Transnational Jihadism. Washington DC, US: Georgetown University Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-1-62616-116-0.

Western colonialists established in these countries political orders... that, even though not professing enmity to Islam and its institutions, left no role for Islam in society. This caused a crisis among Muslim reformists, who felt betrayed not only by the West but also by those nationalists, many of whom were brought to power by the West... Nothing reflects this crisis more than the ideological transformation of Rashid Rida (1865–1935)... He also revived the works of Ibn Taymiyah by publishing his writings and promoting his ideas. Subsequently, taking note of the cataclysmic events brought about by Western policies in the Muslim world and shocked by the abolition of the caliphate, he transformed into a Muslim intellectual mostly concerned about protecting Muslim culture, identity, and politics from Western influence. He supported a theory that essentially emphasized the necessity of an Islamic state in which the scholars of Islam would have a leading role... Rida was a forerunner of Islamist thought. He apparently intended to provide a theoretical platform for a modern Islamic state. His ideas were later incorporated into the works of Islamic scholars. Significantly, his ideas influenced none other than Hassan al-Bannah, founder of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt... The Muslim Brethren have taken up Rida's Islamic fundamentalism, a right-wing radical movement founded in 1928,..

- ↑ "Isis to mint own Islamic dinar coins in gold, silver and copper". The Guardian. 21 November 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/nov/14/isis-gold-silver-copper-islamic-dinar-coins.

- ↑ "Huge rally for Turkish secularism". BBC News. 29 April 2011. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/6604643.stm.

- ↑ Saleh, Heba (15 October 2011). "Tunisia moves against headscarves". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/6053380.stm.

- ↑ "Laying down the law: Islam's authority deficit". The Economist. 28 June 2007. http://www.economist.com/node/9409354?story_id=9409354.

- ↑ Bowering, Gerhard; Mirza, Mahan; Crone, Patricia (2013). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780691134840.

- ↑ Ultraconservative Islam on rise in Mideast. MSNBC (18 October 2008).

- ↑ Almukhtar, Sarah; Peçanha, Sergio; Wallace, Tim (5 January 2016). "Behind Stark Political Divisions, a More Complex Map of Sunnis and Shiites". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/01/04/world/middleeast/sunni-shiite-map-middle-east-iran-saudi-arabia.html.

- ↑ Why the Persecution of Muslims Should Be on Biden's Agenda (English). Foreign Policy Magazine (6 January 2021).

- ↑ Perrin, Andrew (10 October 2003). "Weakness in numbers". Time. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ↑ For China, Islam is a 'mental illness' that needs to be 'cured' (English). Al Jazeera.

- ↑ Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the Twentieth Century. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-4422-0663-2.

- ↑ Oliver Holmes (19 December 2016). "Myanmar's Rohingya campaign 'may be crime against humanity'". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/19/myanmars-rohingya-campaign-may-be-against-humanity.

- ↑ Rohingya abuse may be crimes against humanity: Amnesty (19 December 2016).

- ↑ Report of Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar (27 August 2018).

- ↑ Slackman, Michael (28 January 2007). "In Egypt, a new battle begins over the veil". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/28/weekinreview/28slackman.html.

- ↑ Nigosian (2004), p. 41.

- ↑ "Islamic televangelist; holy smoke". The Economist. http://www.economist.com/node/21534763.

- ↑ Esposito (2010), p. 263.

- ↑ V. Šisler: The Internet and the Construction of Islamic Knowledge in Europe p. 212

- ↑ Esposito (2004), pp. 118–119, 179.

- ↑ Rippin (2001), p. 288.

- ↑ Adams, Charles J. (1983). "Maududi and the Islamic State". In Esposito, John L. (ed.). Voices of Resurgent Islam. Oxford University Press. pp. 113–4.

[Maududi believed that] when religion is relegated to the personal realm, men inevitably give way to their bestial impulses and perpetrate evil upon one another. In fact it is precisely because they wish to escape the restraints of morality and the divine guidance that men espouse secularism.

- ↑ Meisami, Sayeh (2013). 'Abdolkarim Soroush (en).

- ↑ Abdullah Saeed (2017). "Secularism, State Neutrality, and Islam". In Phil Zuckerman; John R. Shook (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Secularism. p. 188. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199988457.013.12. ISBN 978-0-19-998845-7. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2023.Tɛmplet:Subscription required

- ↑ Nader Hashemi (2009). "Secularism". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530513-5. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2023.Tɛmplet:Subscription required

- ↑ Data taken from various sources, see description in link. Wikimedia Commons (22 August 2022).

- ↑ A chirim ya: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpewresearch.orgReligion - ↑ Muslim Population by Country 2023.

- ↑ The Future of the Global Muslim Population (27 January 2011).

- ↑ Muslims and Islam: Key findings in the U.S. and around the world (9 August 2017).

- ↑ Lipka, Michael, and Conrad Hackett. [2015] 6 April 2017. "Why Muslims are the world's fastest-growing religious group Archived 14 Silimin gɔli May 2019 at the Wayback Machine" (data analysis). Fact Tank. Pew Research Center.