Jɛŋkuno

| Yaɣ sheli | domesticated mammal, pet, Felidae |

|---|---|

| Di bukaata | pet, mouser |

| Pilibu saha | 8. millennium BCE |

| Di malila tuma | allergy to cats |

| Ŋun bɔhim ŋa nyɛ | felinology |

| Kumsi malibu | meow, purr |

| Male form of label | tomcat, Kater, maček |

| Sequenced genome URL | http://www.ensembl.org/Felis_catus |

| Unicode bachinima | 🐈, 🐱 |

| Lihigu pubu | Category:Views of cats |

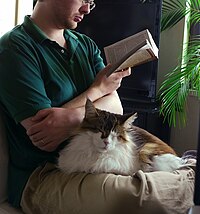

Jaŋkuno[1] nyɛla binkɔbigu bal' shɛli ka o biɛhigu ŋmani Jaŋgbuni. O mali la naba anahi ni ninkpula ka viɣu nina la. Jaŋkuno lahi mali nangban' kob' waɣila ni zu' waɣinli. Jaŋkuno be yiŋa ka bɛ shɛb' lahi be mɔɣini. Yiŋa jaŋkuno nyɛla ninsalinima ni wumsiri shɛba bɛ yinsi.

Jaŋkuno daafaaninima.

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Jaŋkuno nyɛla ŋun gbahiri jaŋgbarisi yili ni.

Jaŋkuno nyɛla daadama yikperilana.

Etymology and naming

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Silimiinsili bachi jaŋkuno pilli, Old English catt, nyɛla bɛ ni mali dihitabili ni di nyɛla din yina Late Latin bachi din nyɛ cattus ka di nyɛ bɛ ni daa na yuuni shɛli bɛ ni boli 6th century piligu.[2] Lala bahigu bachi ŋɔ nyɛla din yina African language.[3] e Nubian ŋɔ bachi kaddîska 'wildcat' mini Nobiin kadīs puuni ka di yina.[4]

Di biɛhigu ŋɔ gba nyɛla din ni tooi yina ancient Germanic bachi din leei Latin ka daa lahi leei Greek, Syriac, nti pahi Arabic.[5] Bachi ŋɔ ni tooi yina Germanic mini Northern European balla ni ka nyɛ bɛ ni paŋ shɛli Uralic, Tɛmplet:Cf.Northern Sámi gáđfi, 'paɣa stoat', mini Hungarian hölgy, 'paɣasaribila, paɣa din nyɛ stoat'; ŋɔ nyɛla din yina Proto-Uralic *käďwä, 'paɣa '.[6]

Silimiinsili bachi din nyɛ puss, nyɛla din tirisi nyɛ pussy mini pussycat ka nyɛ bɛ ni mali dihitabili ni di nyɛla din piligi 16th century ka din daa piligi ni Dutch poes bee ka yina Low German puuskatte amaa ka leei tabi Swedish kattepus, bee Norwegian pus, pusekatt. Di ŋmali nyɛla din be Lithuanian puižė mini Irish puisín bee puiscín. Bachi ŋɔ gbunni nyɛla so ni bi mi shɛli amaa ka nyɛ di ni tooi yina arisen from a sound bɛ ni mali gbaari jaŋkuno .[7][8]

Bɛ booni la jaŋkuno luɣu tom bee tomcat[9] (or a gib,[10] di yi nyɛ neutered). Ka booni jaŋkuno nyaaŋ queen[11][12] (bee saha shɛŋa bɛ tooni booni o molly,[13] di yi nyɛspayed). "juvenile" jaŋkuno ka bɛ booni kitten. Early Modern English, bachi din nyɛ kitten daa nyɛla bachi shɛli bɛ ni daa zaŋ taɣi saha ŋɔ bachi catling.[14] Bɛ booni la Jaŋkun' bɔbugu la clowder, glaring,[15] bee colony.[16]

Taxonomy

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Tabibi yuli Felis catus daa nyɛla Carl Linnaeus daa yɛli shɛli yuuni 1758 zaŋ n-ti yiŋ jaŋkuno.[17][18] Felis catus domesticus nyɛla Johann Christian Polycarp Erxleben ni daa yɛli shɛli yuuni 1777.[19] Felis daemon nyɛla Konstantin Satunin ni daa yɛli shɛli yuuni 1904 daa nyɛla jaŋkun' sabinli ŋun yina Transcaucasus, di nyaaŋa ka bɛ daa yɛli ni o nyɛla yiŋ jaŋkuno.[20][21]

Yuuni 2003, International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature nima daa yɛliya ni yiŋa jaŋkuno ŋɔ nyɛla ŋun yi o konko ka bɛ daa boli o Felis catus.[22][23] Yuuni 2007, saha ŋɔ yiŋ' jaŋkuno F. silvestris catus nyɛla ŋun be dunia luɣili kam ka niriba mali dihitabili ni bɛ nyɛla ban yina African wildcat (F. lybica), ti doli vihigu zaŋ n-ti phylogenetic lahibali.[24][25][lower-alpha 1] Yuuni 2017, IUCN Cat Classification Taskforce nyɛla ban daa doli ICZN ni yɛli shɛm ni yiŋ jaŋkuno ŋɔ nyɛla ŋun yi o konko , Felis catus.[26]

Jaŋkuno balibu

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Jaŋkun' nyaŋ

Jaŋkun' lɔɣu

Jaŋkun' birigu

O zuliya nambu

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Jaŋkuno nyɛla ŋun gba zaani puli, amaa o ni nyɛ binniɛŋ la zuɣu o yi ti mali puli ti yɛrimi ni o malila baɣili dama ninsali ko ka ti ni tooi yɛli ni o malila puli di zuɣu o gba dɔɣirimi. Jaŋkuno yi yɛn dɔɣi,o yɛn nyɛla zimsim shee n-dɔɣi niŋ. Jaŋkuno mi yi dɔɣi bihi, bɛ nina na bɛ ne. Bihi ŋɔ kuli yɛn bela zimsim ŋɔ ni hali ti neei zaa ka naan yi yi polo ni. Hali di yi niŋ daliri ka ninsali baŋ jaŋkun' bihi ŋɔ shee ka bɛ ma ŋɔ nya a, o yɛn zaŋla o noli gbabi ba kahi ba taɣi sɔɣibu shee. Jaŋkuno ŋɔ yɛn dihirila bihi ŋɔ o biha ni (bihim ) hali ti pili ba nima dihibu ka bɛ gba naan ti saɣi bɛ zuɣu bo n-di.

O nyɛvuli tariga ni o daa alaafee

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Jaŋkuno dunia biɛhigu bee nyɛvuli nyɛla din pahi dabisa ŋɔ ni. Yuuni 1980s, di daa nyɛla yuma ayopɔin ,[27]Tɛmplet:Rp[28] amaa ka nyɛ din daa pahi paai 9.4 yuma yuuni 1995[27]Tɛmplet:Rp ka nyɛ din daa lahi pahi paai yuun pia ni ata bin din gbaai yuuni 2014 mini yuuni 2023 sunsuuni.[29][30]

Di nyɛvuli kuli nyɛla din pahira; vihigu zaɣ' yini wuhiya ni jaŋkun' lɔri shɛba bɛ ni ŋmahim nyɛla ban mali jaŋkun' lɔri shɛba bɛ ni bi ŋmahim nyɛvuya ʒibuyi ka jaŋkun' nyama ban bi dɔɣira nyɛla ban nyɛvuya yuuri kamani kɔbigi puuni vaabu 62% gariti jaŋkun' nyama shɛba ban dɔɣira .[27]Tɛmplet:Rp Di yi niŋ ka a zaŋ jaŋkuno neutered nyɛla din mali alaafee anfaani nima kamani nyɛvuli waɣinli ka lahi bɔri o yiriŋyiriŋ dɔɣibu.[31] Amaa a yi lahi zaŋ o niŋ luɣ' yini ŋɔ di chɛrimi ka o bi tooi nyari pɔhim[32][33][34] ka leei pahiri o bindirigu dibu,[34][35] ka di zaa nyɛ din ni tooi che ka o bi ŋmɛlim.[36]

Disease

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Kalinli kamani kɔbigi ni pihinu nyɛla jaŋkun' shɛba ban mali genetic disorders ; di pa nyɛla din ŋmani ninsali nima inborn errors of metabolism.[37] Di ni ŋmani taba ŋɔ tooi che ka bɛ tibiri lala dɔriti ŋɔ binnamda ni ka wunsiri genetic tests shɛli bɛ ni daa tooi niŋ n-ti ninsali nima ka jaŋkunti mi di ni nyɛ animal models ti yi kana ninsalinima dɔriti bɔhimbu puuni .[38][39] Dɔri shɛŋa din tooi gbaari yiŋ' jaŋkunti n-nyɛ, parasitic infestations, dansi nti pahi dɔri yoya kamani kidney disease, thyroid disease nti pahi arthritis. Vaccinations.[40]

Interaction with humans

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Jaŋkunti nyɛla binkɔb' shɛŋa ban yoli dunia zaa ka bɛ kalinli dunia zaa nyɛ bin din gbaari 500 million bin din gbaai yuuni 2007.[41] yiŋ' jaŋkuno n-daa nyɛ binnamdili din kalinli galisi pam m-pahiri ayi United States, ni kalinli din yiɣisi 95.6 million jaŋkunti [42][43] ka yiya kamani 42 million nyɛ din mali kamani jaŋkun' yino yili kam.[44] United Kingdom. Kɔbiga puuni vaabu pishi ni ayobu zaŋ n-ti ninvuɣ' shɛba ban nyɛ zaɣ' kura nyɛla ban mali jaŋkuno ka bɛ kalinli nyɛ kamani 10.9 million bin din gbaai yuuni as of 2020.[update][45] Yuuni 2021, jaŋkun' shɛba ban mali laamba kalinli daa nyɛla din yiɣisi 220 million ka kalinli kamani 480 million daa nyɛ jaŋkun' shɛba ban ka laamba dunia zaa.[46]

Jaŋkunti nyɛla bɛ ni mali shɛba kariti yiŋ binema, around grain stores mini aboard ships ni din kam pahi.[47][48] Jaŋkunti lahi nyɛla bɛ ni wumsiri shɛba fur trade[49] n-ti pahi gbɔŋ tuma yaɣa maani nema, zipilisi, bindɔhi ,[50] namda, nusuriti nti pahi binkumda nema.[51] Jaŋkunti kalinli kamani pishi ni anahi nyɛla bɛ ni tooi zaŋ mali "cat-fur coat".[52] Lala tuma ŋɔ nyɛla bɛ ni daa zaɣisi shɛli United States tum yuuni 2000 and mini European Union (nti pahi United Kingdom) tum yuuni 2007.[53],[54] ka bɛ na kuli nyɛ bɛ ni niŋdi shɛba niŋdi bindɔna nima ni Switzerland ka di nyɛ traditional medicines tibiri rheumatism.[55]

Niriba nyɛla ban mo bushɛm ni niŋ jaŋkunti kalinli yuma din gari maa, di zaa nyɛla laɣinsi bee tiŋgbana mini tiŋduya laɣinsi kamani Canadian Federation of Humane Societies[56] mini pohim zuɣu.[57][58] Bɛ buɣisi ni duniya zaa yiŋ jaŋkunti nyɛla ban kalinli yiɣisi kamani 200 million zaŋ chaŋ 600 million.[59][60][61][62][63]

| Cat Temporal range: Tɛmplet:Geological range

| |

|---|---|

Various types of cats | |

Domesticated

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Missing taxonomy template ([[[:Tɛmplet:Create taxonomy/link]] fix]): | Felis |

| Species: | Template:Taxonomy/FelisF. catus[17]

|

| Binomial name | |

| Template:Taxonomy/FelisFelis catus[17] | |

| Synonyms | |

Bɛ dɔriti gbahibu

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Jaŋkunti ni ni tooi gbaai dɔri shɛŋa n-nyɛ viruses, bacteria, fungus, protozoans, arthropods bee ka bɛ nyɛ ban ni tooi tahi dɔro na n-ti ti ninsalinima bɛ biɛhigu ni bee bɛ ʒilɛli puuni.[64] Saha shɛŋa jaŋkuno ŋɔ ni mali lala dɔro ŋɔ nahingbaŋ.[65] Lala dɔro ŋɔ nyɛla din ni tooi gbaai ninsalinima di yi niŋ ka bɛ mini lala jaŋkuno niŋ niŋgbuna ni taba bee o zaŋ o noli niŋ bɛ bindira ni ka bɛ bi mi ka gba di li .[66] Lala dɔro ŋɔ yi yɛn gbaai ninsala din doli la o yuma mini immune status zaŋ n-ti lala ninsali maa. Ninsali shɛba ban mali jaŋkunti bɛ yinsi bee ka jaŋkunti miri ba nyɛla ban zaa ni tooi gbaai lala dɔro ŋɔ. Lala dɔro ŋɔ gba nyɛla din ni tooi doli jaŋkuno feces gbaagi ninsala.[64][67] Di dɔri shɛŋa din niŋ bayana n-nyɛ; salmonella, cat-scratch disease nti pahi toxoplasmosis.[65]

Evolution

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Yiŋ' jaŋkuno ŋɔ nyɛla ŋun be Felidae, daŋ shɛli din mali common ancestor zaŋ jandi Tɛmplet:Mya.[68] Evolutionary radiation zaŋ n-ti Felidae nyɛla din daa piligi Asia Miocene saha kamani Tɛmplet:Mya.[69] Vihigu zaŋ n-ti mitochondrial DNA n-ti Felidae balli zaa nyɛla din wuhiri Tɛmplet:Mya.[70] Genus Felis genetically diverged din yina Felidae yaɣili kamani Tɛmplet:Mya.[69] Lahibali din yina phylogenetic vihigu wuhiya ni mɔɣuni binkɔbiri ban be lala daŋ ŋɔ ni nyɛla sympatric bee parapatric speciation ka yiŋ' jaŋkuno ŋɔ mi nyɛ artificial selection.[71] Yiŋ' jaŋkuno ŋɔ mini o mɔɣuni binkɔbi so ban ŋmani taba nyɛla diploid ka bɛ zaa mali chromosomes pihinahi ayi ka [72] ka bɛ kalinli nyɛ din ni tooi paai 20,000 laasabu.[73]

| nuclear DNA:[69][70] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| mitochondrial DNA:[74] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Domestication

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Saha waɣala ha di daa wuhiya ni domestication of the cat daa piligi la ancient Egypt, ni ka jaŋkunti daa nyɛ bɛ ni tiri shɛli jilima bin din gbaai 3100 BC.[75][76] Amaa piligu ha taarihi zaŋ jandi yiŋ' jaŋkuno ŋɔ zaŋ n-ti Afirikanima mɔɣuni jaŋkuno daa nyɛla excavated ka miri ninsalinima Neolithic gballi din be Shillourokambos, Cyprus nudirigu zuɣu, bin din gbaai 7500–7200 BC.[77] Tabibi baŋdiba nyɛla ban yɛli ni Afirikanima mɔɣuni jaŋkuno daa nyɛla ŋun yina ninsalinima biɛhigu shee din be Fertile Crescent ka di nyɛla yiŋ' binnema zuɣu balli lee house mouse (Mus musculus) ka Neolithic pukpariba daa baligiba. Lala biɛhishɛli din daa be pukpariba mini jaŋkunti ŋɔ sunsuuni nyɛla din daa ti naai yuun tuhituha nyaaŋa. Kamani pukparilim tuma nima ka bɛ daa zaŋ baligi yiŋ' jaŋkunti ŋɔ.[74][78] Mɔɣuni jaŋkunti zaŋ n-ti Egypt nyɛla din mali tɔhibu ni gene pool zaŋ n-ti yiŋ' jaŋkuno.[79]

Piligu ha shɛhira shɛŋa din be ni zaŋ n-ti yiŋ' jaŋkunti nyɛla Greece kamani1200 BC. Greek, Phoenician, Carthaginian nti pahi Etruscan daabihi n-daa zaŋ yiŋ' jaŋkunti kpɛna Europe nudirigu zuɣu.[80] Bin din gbaai 5th century BC, binkɔbi shɛba daa beni ŋmani ba ka daa be Magna Graecia mini Etruria.[81] Roman Empire saha, bɛ daa zaŋ ba kpɛna Corsica mini Sardinia pɔi ni 1st century AD piligu.[82] Western Roman Empire naabu ni 5th century, Egyptian yiŋ' jaŋkuno birili nyɛla din daa kpeBaltic Sea port din be Germany nuzaa zuɣu la.[79]

Characteristics

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Size

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Yiŋ' jaŋkuno nyɛla ŋun mali zuɣu ŋmaŋ bela mini kɔbi jihi gari European wildcat.[83] Di waɣilim nyɛla din be kamani 46 cm (18 in) bin din gbaai o zuɣu shee zaŋ ni o niŋgbana yɛliŋ ka 23–25 cm (9.1–9.8 in) nyɛ o waɣilim, ka o zuli waɣilim be kamani 30 cm (12 in). Jaŋkun' lɔri nyɛla ban bari gari jaŋkun' nyama.[84] Yiŋ' jaŋkun' kura timsim tooi nyɛla 4–5 kg (8.8–11.0 lb).[71]

I

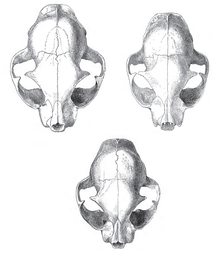

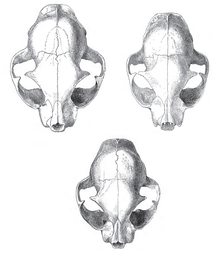

Skeleton

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Jaŋkunti nyɛla ban mali cervical vertebrae dibaa ayopɔin (kamani mammals ni tooi mali li shɛm); thoracic vertebrae pia ni ata (ninsalinima mali la pia ni ayi); lumbar vertebrae dibaa ayopɔin (ninsalinima mali la dibaa anu); sacral vertebrae dibaaata (kamani binvuhirigu kam ni mali li shɛm amaa ninsalinima mali li mi dibaa anu); nti pahi kalinli shɛli caudal vertebrae ka di be zuli maa ni (ninsalinima nyɛla ban mali li dibaa ata zaŋ chaŋ dibaa anu ka di laɣim ni coccyx).[85]Tɛmplet:Rp "lumbar and thoracic vertebrae" shɛli din pahi maa nyɛla din che ka jaŋkuno niŋgbana tooi lɛbigiri ginda. Din tabi yaaŋkobili ŋɔ n-nyɛ sapirikoba pia ni ata, bɔɣisapiŋ nti pahi pelvis.[85]Tɛmplet:Rp kamani ninsali bɔɣu, jaŋkuno nuu nyɛla din tabi bɛ bɔɣisapiŋ ka kɔbi shɛli din gbaai li tabi li ŋɔ yuli booni.[86]

Balance

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Jaŋkunti nyɛla ban tooi yu binyɛri shɛŋa din dɔ zuɣusaa ʒinibu. Zuɣusaa ʒinibu ŋɔ nyɛla din tooi che ka o gbahiri binyɛra ka di bi niŋdi o muɣisigu. Labisiri shɛli din ni tooi lahi zaŋ n-ti jaŋkuno zuɣusaa ʒinibu ŋɔ n-nyɛ di chɛmi ka o tooi lihiri gindi luɣilikam viɛnyɛla ka bini kam din be katiŋa o nyɛla ŋun yɛn tooi lihi gbaai lala bini maa. Jaŋkuno ŋun yi zuɣusaa kamani 3 m (9.8 ft) lurina nyɛla ŋun ni tooi lɛbigi o maŋ zani tiŋgbani ni.[87]

Di yi ti niŋ ka jaŋkuno yi zuɣuzaa lurina tiŋ' pirimla o niŋgbana ni nyɛ din bali la zuɣu o nyɛla o ŋun yɛn lɛbi lɛbi o maŋ hali ti zani o naba zuɣu, lala zanibu ŋɔ ka bɛ booni cat righting reflex.[88] Jaŋkuno nyɛla ŋun ni tooi lɛbigi o maŋ ka nyɛ ŋun ni tooi niŋ li hali o yi lurina zuɣusaa din paai kamani 90 cm (3.0 ft) bee ka di gari.[89] Jaŋkuno ni tooi lɛbigiri o maŋ shɛm di yi ti niŋ ka o lurina nyɛla bɛ ni daa niŋ shɛli vihigu ka boli "falling cat problem".[90]

| nuclear DNA:[69][70] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| mitochondrial DNA:[74] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ecology

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Habitats

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Yiŋ' jaŋkuno ŋɔ nyɛla cosmopolitan species ka nyɛ ban be dunia luɣilikam.[91] Di bi piiri binshɛli ka nyɛ din pa be luɣilikam gbaai yihi Antarctica, nti pahi 118 zaŋ chaŋ 131zaŋ n-ti islands, hali Kerguelen Islands.[92][93] Pirimla di nyɛla luɣ' shɛli din tooi mali binnema pam di zuɣu di nyɛla din pahi dunia invasive species.[94] Di nyɛla din be islands bihi ni luɣ' shɛli ninsalinima ni kani.[95] Feral jaŋkunti nyɛla ban be tibɔna ni, mɔri ni, "tundra", pukparilim tiŋgbani ni, fɔŋ ni nti pahi kom ni zooi tiŋgbani shɛŋa ni.[96]

Pirimla bɛ daa je o zuɣu n-daa su yiŋ' jaŋkuno ni treated as an invasive species. Dinbɔŋɔ nyɛla hybridization din mali barina zaŋ jaŋkun' biriti balantee ban be Scotland nti pahi Hungary, di pa shɛli ni Iberian Peninsula, ni luɣ' shɛŋa bɛ gu ka taɣi ka di nyɛ din miri Kruger National Park din be South Africa.[97][98]

Ferality

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Feral jaŋkunti nyɛla yiŋ' jaŋkun' shɛba balanlee jaŋkun' biriti . Bɛ nyɛla ban bi miriti ninsalinima ka nyɛ ban be fɔna ni mini tiŋkpansi.[99] Jaŋkun' biriti ŋɔ kalinli nyɛla niriba ni bi mi shɛli amaa bɛ buɣisi ni United States jaŋkun' biriti kalinli nyɛla bin din gbaai miliyɔŋ pishi ni anu zaŋ chaŋ miliyɔŋ pihiyobu.[99] Jaŋkun' biriti ŋɔ nyɛla ban ni tooi be bɛ koŋko amaa bɛ pam nyɛla ban tooi be colonies kara ni.[100] Jaŋkun' biriti pam tooi zooya ka bɛ be Rome kamani Colosseum mini Forum Romanum, ka jaŋkunti ban be ni ŋɔ nyɛla bɛ ni dihiri shɛba ka bɔri alaafee n-tiri ba biɛɣukulo.[101]

Salo biɛhigu ni jaŋkun' biriti nyɛla din wali, pirimla so bi wumsiri lala jaŋkun' biriti ŋɔ zuɣu niriba pam nya o mi vermin.[102]

Impact on wildlife

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Island nima ni, noonsi tɔhibu zaŋ ti jaŋkun' biriti bindirigu nyɛla kamani kɔbigi puuni vaabu pihiyɔbu 60%.[103] Luɣilikam vihigu wuhiya ni noonsi kalinli boobu daliri pala jaŋkun' biriti amaa jaŋkun' biriti pam kpibu daliri nyɛla "mesopredator release";[104] Yiŋ jaŋkunti nyɛla ban tɔhiri pahiri bineembihi kalinli boobu ni. The South Island piopio, Chatham rail,[105] nti pahi New Zealand merganser[106] nyɛla din pahi luɣ' shɛŋa din nyɛ "flightless" Lyall's wren.[107][108] Jaŋkun' biri yino New Zealand nyɛla ŋun daa ku New Zealand lesser short-tailed bats kɔbigi ni dibaa ayi dabaa ayopɔin sunsuuni.[109] United States, jaŋkun' biriti mini yiŋ' jaŋkunti nyɛla ban kuri bineembihi kalinli kamani 6.3–22.3 billion yuuni kam.[110]

Australia, vihigu zaɣ' yini wuhiya ni jaŋkun' biriti nyɛla ban kuri bineembihi shɛba ban be kom ni ka lahi be duli zuɣu kalinli kamani 466 million yuuni kam. Kalinli kamani kɔbishii ni pihiyɔbu ayi ka "reptiles" nyɛla bɛ ni daa nya shɛba ni kpi ka di nyɛla jaŋkun' biriti n-ku ba.[111] Jaŋkunti nyɛla ban tɔhi pahi Navassa curly-tailed lizard mini Chioninia coctei kalinli boobu ni.[112]

-

A 19th-century drawing of a tabby cat

-

Some cultures are superstitious about black cats, ascribing either good or bad luck to them.

Biɛhigu

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Jaŋkun' shɛba ban be luɣ' yini nyɛla ban mali yaa wuntaŋ ni mini yuŋ zaa amaa ka leei mali yaa pam yuŋ.[114] Yiŋ' jaŋkunti nyɛla ban tooi kuri bɛ saha pam be yiŋ' amaa ka ni tooi chaŋ n-gili kamani mita kɔbiga. Bɛ galisim nyɛla din wali bee pa yim, shɛba galisim nyɛla 7–28 ha (17–69 acres).[115] Jaŋkunti zaa tuma pa yim ka nyɛ din woli woli taba amaa ka bɛ tuumbiɛri bala. Yaha, yiŋ' jaŋkunti biɛhigu doli la ninsalinima ni be ba shɛm ka nyɛ ban ni tooi gbihiri ni bɛ laamba hali ni saha shɛli bɛ suhu ni bɔra.[116][117]

Play

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Yiŋ jɛŋkunti, bahindi la jɛŋkuno bihi nyɛla ban bori diɛma pam. Lala biɛhigu ŋɔ nyɛla din tɔɣisiri gbaabu ka di nyɛ din viɛlli pam zaŋ n-ti jɛŋkuno bihi dama di nyɛla din wuhiri ba puɣisibu, gbaabu n-ti pahi bineema kubu.[118] Jɛŋkunti nyɛla ban lahi niŋdi diɛma zabili ka bɛ zaa gbubi mali bɛ nuhi mini bɛ niŋgbana zaa zabiri taba. Lala biɛhigu ŋɔ nyɛla biɛhi shɛli di ni tooi che ka jɛŋkunti baŋ zabili zabu ni bori binshɛŋa zaa ka lahi bori dabiɛm bɛ ni ni binkɔbi shɛŋa ti ni gbaai ba.[119]

Jɛŋkunti nyɛla ban diɛmdi binyɛra pam saha shɛli o suhi yi ti yiɣisi.[120] O diɛma nyɛla din ŋmani o binyɛra gbaabu, jɛŋkunti tooi zooi ka o diɛmdi binshɛŋa din ŋmani bingbaarigu kamani "small furry toys" din chani ginda. Bɛ nyɛla ban yooi binyɛri shɛŋa bɛ ni na mi pun diɛm diɛmbu.[121] Mia nyɛla bɛ ni tooi diɛmdi binshɛli amaa di yi ti niŋ ka o dim ŋmaai mia ŋɔ niriba ni tooi yihi li na o zinli zuɣu amaa di yi niŋ ka faai lu o binnyɔri ni shee be m-bo tilaa n-ti o ka di ni tooi che ka o kpi.[122] Pirinla jɛŋkuno ni tooi vali lala mia ŋɔ zuɣu, saha shɛŋa bɛ tooi mali laser pointerTɛmplet:'s zaani di zani.[123]

Reproduction

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

Jɛŋkuno nyɛla pheromones.[124] Jɛŋkuno nyama ka bɛ booni ba queens nyɛla polyestrous mini estrus nima pam tooi booyi booyi bɛ zuɣu ka di tooi naari kamani biɛɣ'pishi ni yini dabisa. Bɛ nyɛla ban tooi niŋdi shili ni laɣimbu silimiin goli February piligu mini silimiin goli August[125] [126]

Jɛŋkuno lɔri pam nyɛla bɛ ni booni shɛba tomcats, nyɛla ban laɣindi jɛŋkuno nyamma tulim ni. Bɛ nyɛla ban zabiri taba jɛŋkuno nyaŋ ŋɔ zuɣu ka ŋun di nasara nyɛ ŋun yɛn laɣim jɛŋkuno nyaŋ ŋɔ. Tuuli, jɛŋkuno nyaŋ ŋɔ nyɛla ŋun yɛn zaɣisi jɛŋkuno lɔɣu ŋɔ amaa ka leei ti che ka jeŋkuno lɔɣu ŋɔ laɣim ŋɔ. Jɛŋkuno nyaŋ ŋɔ nyɛla ŋun yɛn kuhi pam di yi niŋ ka jɛŋkuno lɔɣu maa yihi o yoli dama o yoli maa nyɛla din mali "band" ka di be kamani 120–150 "backward-pointing penile spines" ka di waɣilim be kamani 1 mm (0.039 in).[127]

Senses

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Vision

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Jɛŋkunti nyɛla ban mali night vision pam nyɛ ban ni tooi nya kalinli dibaa ayobu puuni kalinli zaɣ'yini ninsali nyabu puuni.[128]Tɛmplet:Rp Din bɔŋɔ daliri nyɛla jɛŋkuno nina mali la tapetum lucidum ka di nyɛlisiri neesim kam di yi nya retina ka labi nini maa ni, lala zuɣu ka di pahiri nini maa neeisim nyɛlisibu.[129] ''Large pupils" nyɛla ban nina fulimbu bɛ to. Yiŋ jɛŋkuno nyɛla ŋun mali slit pupils ka di che ka bɛ tooi nyari neeisim hali chromatic aberration yi kani.[130] Neeisim dinpori ni, jɛŋkuno "pupils" nyɛla din yɛligiri gbaari ninbila maa zaa.[131] Yiŋ jɛŋkuno ŋɔ leei mali color vision din bi viɛlla ka lahi mali cone cells balibu dibaa ayi koŋko ka di tooi che ka o nyari kama din nyɛ nuɣiso, dɔzim; bɛ bi tooi waligiri kama din nyɛ ʒee mini vakahili.[132] [133] Jɛŋkunti gba lahi nyɛla nictitating membrane.

Hearing

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Yiŋ jɛŋkunti nyɛla ban wumdi pam ka bɛ wumbu ŋɔ be kamani 500 Hz zaŋ hali ni 32 kHz.[134] Bɛ nyɛla ban ni tooi nya bini din yɛliŋ paai kamani 55 Hz zaŋ hali ni 79 kHz amaa ninsali nima nyɛla ban ni tooi nya bini yɛliŋ bin din gbaai 20 Hz mini 20 kHzn sunsuun. Bɛ ni tooi wum kamani 10.5 octaves ka ninsali nima mini bahi nyɛ ban ni tooi wum kamani 9 octaves.[135][136] Bɛ nyabu nyɛla din pahira ka din pahiri ŋɔ nyɛ bɛ tibi kara din chani ginda, pinnae ka di sɔŋdiba ka bɛ wumdi kumsim ka tooi baŋdi lala kumsim maa ni yiri luɣ'shɛli na.[137][138] Saha ŋɔ vihigu nyɛla din wuhi ni jɛŋkunti nyɛla ban mali "socio-spatial cognitive abilities" ka di sɔŋdiba ka bɛ baŋdi niriba yɛltɔɣa.[139]

Lihimi m-pahi

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Lua bi niŋ dede:bad argument #2 to 'title.new' (unrecognized namespace name 'Portal')

- Aging in cats

- Ailurophobia

- Animal testing on cats`

- Cancer in cats

- Cat bite

- Cat café

- Cat collar

- Cat fancy

- Cat lady

- Cat food

- Cat meat

- Cat repeller

- Cats and the Internet

- Cats in Australia

- Cats in New Zealand

- Cats in the United States

- Cat–dog relationship

- Dog

- Dried cat

- Feral cats in Istanbul

- List of cat breeds

- List of cat documentaries, television series and cartoons

- List of individual cats

- List of fictional felines

- List of feline diseases

- Neko-dera

- Perlorian

- Pet door

- Pet first aid

- Popular cat names

Notes

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]- ↑ Naden, Tony. 2020. Pictures and words, Dagbani Dictionary.

- ↑ McKnight, G. H. (1923). "Words and Archaeology". English Words and Their Background. New York, London: D. Appleton and Company. pp. 293–311.

- ↑ Pictet, A. (1859). Les origines indo-européennes ou les Aryas primitifs : essai de paléontologie linguistique (in French). 1. Paris: Joël Cherbuliez. p. 381.

- ↑ Keller, O. (1909). Die antike Tierwelt (in German). Säugetiere. Leipzig: Walther von Wartburg. p. 75.

- ↑ Huehnergard, J. (2008). "Qitta: Arabic Cats". In Gruendler, B.; Cooperson, M. (eds.). Classical Arabic Humanities in Their Own Terms: Festschrift for Wolfhart Heinrichs on his 65th Birthday. Leiden, Boston: Brill. pp. 407–418. ISBN 9789004165731. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ Kroonen, G. (2013). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. p. 281f. ISBN 9789004183407.

- ↑ Puss. The Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ "puss". Webster's Encyclopedic Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language. New York: Gramercy (Random House). 1996. p. 1571.

- ↑ tom cat, tom-cat. The Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ gib, n.2. The Oxford English Dictionary.

- ↑ queen cat. The Oxford English Dictionary.

- ↑ Some sources wrote that queen refers to unspayed cats that are in an oestrus cycle. Grosskopf, Shane (23 June 2022). What is a Female Cat Called? A Guide to the Fascinating Terms. Scamporrino, Christina (12 December 2018). Cat Parenting 101: Special Considerations for Your Female Cat.

- ↑ 7 fascinating facts about female cats (en) (March 8, 2020).

- ↑ catling. The Oxford English Dictionary.

- ↑ What do you call a group of ...?. Oxford Dictionaries Online. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Terms we use for cats.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis Catus". Systema naturae per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). 1 (10th reformed ed.). Holmiae: Laurentii Salvii. p. 42.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Tɛmplet:MSW3 Wozencraft

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Erxleben, J. C. P. (1777). "Felis Catus domesticus". Systema regni animalis per classes, ordines, genera, species, varietates cvm synonymia et historia animalivm. Classis I. Mammalia. Lipsiae: Weygandt. pp. 520–521.

- ↑ (1904) "The Black Wild Cat of Transcaucasia". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London II: 162–163.

- ↑ Bukhnikashvili, A.; Yevlampiev, I. (eds.). Catalogue of the Specimens of Caucasian Large Mammalian Fauna in the Collection (PDF). Tbilisi: National Museum of Georgia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ↑ (2003) "Opinion 2027". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 60.

- ↑ (2004) "The naming of wild animal species and their domestic derivatives". Journal of Archaeological Science 31 (5): 645–651. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2003.10.006.

- ↑ (2009) "In the Light of Evolution III: Two Centuries of Darwin Sackler Colloquium: From Wild Animals to Domestic Pets – An Evolutionary View of Domestication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (S1): 9971–9978. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0901586106. PMID 19528637.

- ↑ Tɛmplet:MSW3 Wozencraft

- ↑ (2017) "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group". Cat News Special Issue 11.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Kraft, W. (1998). "Geriatrics in canine and feline internal medicine". European Journal of Medical Research 3 (1–2): 31–41. PMID 9512965.

- ↑ (1984) "Study of the feline and canine populations in the greater Las Vegas area". American Journal of Veterinary Research 45 (2): 282–287. PMID 6711951.

- ↑ (2014) "Longevity and mortality of cats attending primary care veterinary practices in England". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 17 (2): 125–133. DOI:10.1177/1098612X14536176. PMID 24925771.

- ↑ (2023) "Life expectancy tables for dogs and cats derived from clinical data". Frontiers in Veterinary Science 10: 1082102. DOI:10.3389/fvets.2023.1082102. PMID 36896289.

- ↑ (14 January 2020) "Neutering in dogs and cats: current scientific evidence and importance of adequate nutritional management". Nutrition Research Reviews 33 (1): 134–144. DOI:10.1017/s0954422419000271. ISSN 0954-4224. PMID 31931899.

- ↑ (1 May 2002) "Effects of neutering on hormonal concentrations and energy requirements in male and female cats". American Journal of Veterinary Research 63 (5): 634–639. DOI:10.2460/ajvr.2002.63.634. ISSN 0002-9645. PMID 12013460.

- ↑ (2001) "Effects of feeding regimens on bodyweight, composition and condition score in cats following ovariohysterectomy". Journal of Small Animal Practice 42 (9): 433–438. DOI:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2001.tb02496.x. ISSN 0022-4510. PMID 11570385.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 (1997) "Effects of neutering on bodyweight, metabolic rate and glucose tolerance of domestic cats". Research in Veterinary Science 62 (2): 131–136. DOI:10.1016/s0034-5288(97)90134-x. ISSN 0034-5288. PMID 9243711.

- ↑ (2003) "Weight Gain in Gonadectomized Normal and Lipoprotein Lipase–Deficient Male Domestic Cats Results from Increased Food Intake and Not Decreased Energy Expenditure". The Journal of Nutrition 133 (6): 1866–1874. DOI:10.1093/jn/133.6.1866. ISSN 0022-3166. PMID 12771331.

- ↑ (19 January 2018) "Overweight in adult cats: a cross-sectional study". Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 60 (1). DOI:10.1186/s13028-018-0359-7. ISSN 1751-0147. PMID 29351768.

- ↑ (2008) "State of Cat Genomics". Trends in Genetics 24 (6): 268–279. DOI:10.1016/j.tig.2008.03.004. PMID 18471926.

- ↑ (2007) "Inherited Metabolic Disease in Companion Animals: Searching for Nature's Mistakes". Veterinary Journal 174 (2): 252–259. DOI:10.1016/j.tvjl.2006.08.017. PMID 17085062.

- ↑ (2002) "The Feline Genome Project". Annual Review of Genetics 36: 657–686. DOI:10.1146/annurev.genet.36.060602.145553. PMID 12359739.

- ↑ Huston, L. (2012). Veterinary Care for Your New Cat. PetMD.

- ↑ Wade, N. (2007). "Study Traces Cat's Ancestry to Middle East". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/29/science/29cat.html.

- ↑ Pet Industry Market Size & Ownership Statistics. American Pet Products Association.

- ↑ The 5 Most Expensive Cat Breeds in America. moneytalksnews.com (2017).

- ↑ 61 Fun Cat Statistics That Are the Cat's Meow! (2022 UPDATE) (12 December 2020).

- ↑ How many pets are there in the UK?.

- ↑ Statistics on cats (2021).

- ↑ Beadle, Muriel (1979). Cat. Simon and Schuster. pp. 93–96. ISBN 9780671251901.

- ↑ Mayers, Barbara (2007). Toolbox: Ship's Cat on the Kalmar Nyckel. Bay Oak Publishers. ISBN 9780974171395. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ↑ What Is That They're Wearing?. Humane Society of the United States.

- ↑ Stallwood, K. W., ed. (2002). A Primer on Animal Rights: Leading Experts Write about Animal Cruelty and Exploitation. Lantern Books.

- ↑ "Japan: Finale for the world's most elegant use of a dead cat". The Independent. 15 November 1997. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/japan-finale-for-the-worlds-most-elegant-use-of-a-dead-cat-1294096.html.

- ↑ "EU proposes cat and dog fur ban". BBC News. 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6165786.stm.

- ↑ Ikuma, C. (2007). EU Announces Strict Ban on Dog and Cat Fur Imports and Exports. Humane Society International.

- ↑ Jolly, K. L.; Raudvere, C.; Peters, E. (2002). Witchcraft and Magic in Europe. 3: The Middle Ages. London: Athlone. ISBN 9780567574466. OCLC 747103210.

- ↑ Paterson, T. (2008). "Switzerland Finds a Way to Skin a Cat for the Fur Trade and High Fashion". The Independent (London). https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/switzerland-finds-a-way-to-skin-a-cat-for-the-fur-trade-and-high-fashion-815426.html.

- ↑ "Humane society launches national cat census". CBC News. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/story/2012/07/17/nb-cat-census-1000.html.

- ↑ Cats Be.

- ↑ The Supreme Cat Census.

- ↑ About Pets. IFAHEurope.org. Animal Health Europe.

- ↑ Legay, J. M. (1986). "Sur une tentative d'estimation du nombre total de chats domestiques dans le monde" (in fr). Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série III 303 (17): 709–712. PMID 3101986. Tɛmplet:INIST.

- ↑ Gehrt, S. D.; Riley, S. P. D.; Cypher, B. L. (2010). Urban Carnivores: Ecology, Conflict, and Conservation. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801893896. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ↑ Rochlitz, I. (2007). The Welfare of Cats. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781402032271. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ↑ Cats: Most interesting facts about common domestic pets. Pravda (9 January 2006).

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Chomel, B. (2014). "Emerging and Re-Emerging Zoonoses of Dogs and Cats". Animals 4 (3): 434–445. DOI:10.3390/ani4030434. ISSN 2076-2615. PMID 26480316.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Cats. Ohio Department of Health (21 January 2015).

- ↑ (2015) "Diseases Transmitted by Cats". Microbiology Spectrum 3 (5). DOI:10.1128/microbiolspec.iol5-0013-2015. ISSN 2165-0497. PMID 26542039.

- ↑ (2015) "Reducing the risk of pet-associated zoonotic infections". Canadian Medical Association Journal 187 (10): 736–743. DOI:10.1503/cmaj.141020. ISSN 0820-3946. PMID 25897046.

- ↑ (1997) "Phylogenetic Reconstruction of the Felidae Using 16S rRNA and NADH-5 Mitochondrial Genes". Journal of Molecular Evolution 44 (S1): S98–S116. DOI:10.1007/PL00000060. PMID 9071018.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 69.3 (2006) "The late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: A genetic assessment". Science 311 (5757): 73–77. DOI:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 Li, G. (2016). "Phylogenomic evidence for ancient hybridization in the genomes of living cats (Felidae)". Genome Research 26 (1): 1–11. DOI:10.1101/gr.186668.114. PMID 26518481.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 (2000) "Phylogeny and speciation of Felids". Cladistics 16 (2): 232–253. DOI:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2000.tb00354.x. PMID 34902955.

- ↑ (2002) "The genome phylogeny of domestic cat, red panda and five Mustelid species revealed by comparative chromosome painting and G-banding". Chromosome Research 10 (3): 209–222. DOI:10.1023/A:1015292005631. PMID 12067210.

- ↑ (2007) "Initial sequence and comparative analysis of the cat genome". Genome Research 17 (11): 1675–1689. DOI:10.1101/gr.6380007. PMID 17975172.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 (2007) "The Near Eastern Origin of Cat Domestication". Science 317 (5837): 519–523. DOI:10.1126/science.1139518. PMID 17600185.

- ↑ Langton, N.; Langton, M. B. (1940). The Cat in ancient Egypt, illustrated from the collection of cat and other Egyptian figures formed. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Malek, J. (1997). The Cat in Ancient Egypt (Revised ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ↑ (2004) "Early taming of the cat in Cyprus". Science 304 (5668). DOI:10.1126/science.1095335. PMID 15073370.

- ↑ (2009) "The taming of the cat". Scientific American 300 (6): 68–75. DOI:10.1038/scientificamerican0609-68. PMID 19485091.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 (2017) "The palaeogenetics of cat dispersal in the ancient world". Nature Ecology & Evolution 1 (7). DOI:10.1038/s41559-017-0139.

- ↑ (2009) "An archaeological and historical review of the relationships between Felids and people". Anthrozoös 22 (3). DOI:10.2752/175303709X457577.

- ↑ (1994) "The wildcat in central-northern Italian peninsula: a biogeographical dilemma". Biogeographia 17 (1). DOI:10.21426/B617110417.

- ↑ (1992) "Zooarchaeology and the biogeographical history of the mammals of Corsica and Sardinia since the last ice age". Mammal Review 22 (2): 87–96. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2907.1992.tb00124.x.

- ↑ O'Connor, T. P. (2007). "Wild or domestic? Biometric variation in the cat Felis silvestris". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 17 (6): 581–595. DOI:10.1002/oa.913.

- ↑ Sunquist, M.; Sunquist, F. (2002). "Domestic cat". Wild Cats of the World. University of Chicago Press. pp. 99–112. ISBN 9780226779997.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Walker, W.F. (1982). Study of the Cat with Reference to Human Beings (4th revised ed.). Thomson Learning/Cengage. ISBN 9780030579141.

- ↑ Cat Skeleton. Zoolab. University of Wisconsin Press (2002).

- ↑ (September 2010) "The neurology of balance: Function and dysfunction of the vestibular system in dogs and cats". The Veterinary Journal 185 (3): 247–249. DOI:10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.10.029. PMID 19944632.

- ↑ (1957) "The labyrinthine posture reflex (righting reflex) in the cat during weightlessness". The Journal of Aviation Medicine 28 (4): 345–355. PMID 13462942.

- ↑ Nguyen, H. D. (1998). How does a cat always land on its feet?. Georgia Institute of Technology. Tɛmplet:Tertiary source

- ↑ Batterman, R. (2003). "Falling cats, parallel parking, and polarized light". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 34 (4): 527–557. DOI:10.1016/s1355-2198(03)00062-5.

- ↑ A chirim ya: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLipinski - ↑ Say, L. (2002). "Spatio-temporal variation in cat population density in a sub-Antarctic environment". Polar Biology 25 (2): 90–95. DOI:10.1007/s003000100316.

- ↑ (2005) "Biological Invasions in the Antarctic: Extent, Impacts and Implications". Biological Reviews 80 (1): 45–72. DOI:10.1017/S1464793104006542. PMID 15727038.

- ↑ (2011) "A global review of the impacts of invasive cats on island endangered vertebrates". Global Change Biology 17 (11): 3503–3510. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02464.x.

- ↑ (2004) "A Review of Feral Cat Eradication on Islands". Conservation Biology 18 (2): 310–319. DOI:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00442.x.

- ↑ Invasive Species Specialist Group (2006). Ecology of Felis catus. Global Invasive Species Database. Species Survival Commission, International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ (19 August 2014) "Genetic analysis shows low levels of hybridization between African wildcats (Felis silvestris lybica) and domestic cats (F. s. catus) in South Africa". Ecology and Evolution 5 (2): 288–299. DOI:10.1002/ece3.1275. PMID 25691958.

- ↑ (2008) "Hybridization Versus Conservation: Are Domestic Cats Threatening the Genetic Integrity of Wildcats (Felis silvestris silvestris) in Iberian Peninsula?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 363 (1505): 2953–2961. DOI:10.1098/rstb.2008.0052. PMID 18522917.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Rochlitz, I. (2007). The Welfare of Cats. "Animal Welfare" series. Berlin: Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 141–175. ISBN 9781402061431. OCLC 262679891.

- ↑ What is the difference between a stray cat and a feral cat?. HSUS.org. Humane Society of the United States (2 January 2008).

- ↑ Torre Argentina cat shelter..

- ↑ Slater, Margaret R.; Shain, Stephanie (November 2003). "Feral Cats: An Overview (4)" (PDF). In Rowan, Andrew N.; Salem, Deborah J. (eds.). The State of the Animals II: 2003. Humane Society of the United States. ISBN 9780965894272. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2006.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, M. B.; Turner, Dennis C. "Hunting Behaviour of Domestic Cats and Their Impact on Prey Populations". In Turner, Dennis C.; Bateson, Patrick P. G. (eds.). The Domestic Cat: The Biology of its Behaviour. pp. 151–175.

- ↑ (1999) "Cats protecting birds: Modelling the mesopredator release effect". Journal of Animal Ecology 68 (2): 282–292. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2656.1999.00285.x.

- ↑ A chirim ya: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMead 1982 183–186 - ↑ Stattersfield, A. J.; Crosby, M. J.; Long, A. J.; Wege, D. C. (1998). Endemic Bird Areas of the World: Priorities for Biodiversity Conservation. "BirdLife Conservation" series No. 7. Cambridge, England: Burlington Press. ISBN 9780946888337.

- ↑ Falla, R. A. (1955). New Zealand Bird Life Past and Present. Cawthron Institute.[page needed]

- ↑ (2004) "The Tale of the Lighthouse-keeper's Cat: Discovery and Extinction of the Stephens Island Wren (Traversia lyalli)". Notornis 51: 193–200.

- ↑ (2012) "Cat predation of short-tailed bats (Mystacina tuberculata rhyocobia) in Rangataua Forest, Mount Ruapehu, Central North Island, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Zoology 39 (3): 257–260. DOI:10.1080/03014223.2011.649770.

- ↑ A chirim ya: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedNC012913 - ↑ (2018) "How many reptiles are killed by cats in Australia?". Wildlife Research 45 (3). DOI:10.1071/wr17160. ISSN 1035-3712.

- ↑ (2016) "Invasive predators and global biodiversity loss". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113 (40): 11261–11265. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1602480113. PMID 27638204.

- ↑ Clutton-Brock, J. (1999) [1987]. "Cats". A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 133–140. ISBN 9780521634953. OCLC 39786571. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ (2008) "Spatio-temporal Sharing between the European Wildcat, the Domestic Cat and their Hybrids". Journal of Zoology 276 (2): 195–203. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00479.x.

- ↑ Barratt, D. G. (1997). "Home Range Size, Habitat Utilisation and Movement Patterns of Suburban and Farm Cats Felis catus". Ecography 20 (3): 271–280. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0587.1997.tb00371.x.

- ↑ (1985) "Circadian rhythms in food intake and activity in domestic cats". Behavioral Neuroscience 99 (6): 1162–1175. DOI:10.1037/0735-7044.99.6.1162. PMID 3843546.

- ↑ Ling, Thomas (2 June 2021). Why do cats sleep so much?.

- ↑ (1982) "Nonhuman Primate Learning: The Importance of Learning from an Evolutionary Perspective". Anthropology and Education Quarterly 13 (2): 133–148. DOI:10.1525/aeq.1982.13.2.05x1830j.

- ↑ Hall, S. L. (1998). "Object play by adult animals". In Byers, J. A.; Bekoff, M. (eds.). Animal Play: Evolutionary, Comparative, and Ecological Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. pp. 45–60. ISBN 9780521586566. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ Hall, S. L. (1998). "The Influence of Hunger on Object Play by Adult Domestic Cats". Applied Animal Behaviour Science 58 (1–2): 143–150. DOI:10.1016/S0168-1591(97)00136-6.

- ↑ Hall, S. L. (2002). "Object Play in Adult Domestic Cats: The Roles of Habituation and Disinhibition". Applied Animal Behaviour Science 79 (3): 263–271. DOI:10.1016/S0168-1591(02)00153-3.

- ↑ MacPhail, C. (2002). "Gastrointestinal obstruction". Clinical Techniques in Small Animal Practice 17 (4): 178–183. DOI:10.1053/svms.2002.36606. PMID 12587284.

- ↑ Fat Indoor Cats Need Exercise. Pocono Record (2006).Tɛmplet:Tertiary source

- ↑ (1979) "Tom-cat odour and other pheromones in feline reproduction". Veterinary Science Communications 3 (1): 125–136. DOI:10.1007/BF02268958.

- ↑ (1977) "A survey of sexual behaviour and reproduction of female cats". Journal of Small Animal Practice 18 (1): 31–37. DOI:10.1111/j.1748-5827.1977.tb05821.x. PMID 853730.

- ↑ Johnson, A.K; Kutzler, M.A, eds. (2022). "Feline Estrous Cycle". Feline Reproduction. pp. 11–22. doi:10.1079/9781789247107.0002. ISBN 9781789247084. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ↑ (1967) "Penile Spines of the Domestic Cat: Their Endocrine-behavior Relations". The Anatomical Record 157 (1): 71–78. DOI:10.1002/ar.1091570111. PMID 6030760.

- ↑ A chirim ya: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCase - ↑ (2004) "Comparative morphology of the Tapetum Lucidum (among selected species)". Veterinary Ophthalmology 7 (1): 11–22. DOI:10.1111/j.1463-5224.2004.00318.x. PMID 14738502.

- ↑ (2006) "Pupil shapes and lens optics in the eyes of terrestrial vertebrates". Journal of Experimental Biology 209 (1): 18–25. DOI:10.1242/jeb.01959. PMID 16354774.

- ↑ (1985) "The relationship between feline pupil size and luminance". Experimental Brain Research 59 (3): 485–490. DOI:10.1007/BF00261338. PMID 4029324.

- ↑ (1978) "Cat color vision: The effect of stimulus size". Science 199 (4334): 1221–1222. DOI:10.1126/science.628838. PMID 628838.

- ↑ (1993) "The spectral sensitivity of dark- and light-adapted cat retinal ganglion cells". Journal of Neuroscience 13 (4): 1543–1550. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01543.1993. PMID 8463834.

- ↑ Heffner, R. S. (1985). "Hearing range of the domestic cat". Hearing Research 19 (1): 85–88. DOI:10.1016/0378-5955(85)90100-5. PMID 4066516.

- ↑ Heffner, H. E. (1998). "Auditory awareness". Applied Animal Behaviour Science 57 (3–4): 259–268. DOI:10.1016/S0168-1591(98)00101-4.

- ↑ Heffner, R. S. (2004). "Primate hearing from a mammalian perspective". The Anatomical Record Part A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology 281 (1): 1111–1122. DOI:10.1002/ar.a.20117. PMID 15472899.

- ↑ Sunquist, M.; Sunquist, F. (2002). "What is a Cat?". Wild Cats of the World. University of Chicago Press. pp. 5–18. ISBN 9780226779997. Archived from the original on 19 July 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ Blumberg, M. S. (1992). "Rodent ultrasonic short calls: Locomotion, biomechanics, and communication". Journal of Comparative Psychology 106 (4): 360–365. DOI:10.1037/0735-7036.106.4.360. PMID 1451418.

- ↑ (2021) "Socio-spatial cognition in cats: Mentally mapping owner's location from voice". PLOS ONE 16 (11). DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0257611. PMID 34758043.

Kundivihira

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]External links

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Spoken Wikipedia/configuration' not found.

The dictionary definition of cat at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of cat at Wiktionary Data related to Felis catus at Wikispecies

Data related to Felis catus at Wikispecies- Tɛmplet:Commons-inline

- Tɛmplet:Wikibooks inline

Quotations related to Jɛŋkuno at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Jɛŋkuno at Wikiquote- Tɛmplet:Cite Americana

- Biodiversity Heritage Library bibliography for Felis catus

- View the cat genome in Ensembl

- High-resolution images of the cat's brain

- Scientific American. "The Origin of the Cat". 1881. p. 120.

Tɛmplet:Cat nav Tɛmplet:Carnivora

Kundivihira

[mali niŋ | mali mi di yibu sheena n-niŋ]

A chirim ya: &It;ref> tuma maa yi laɣingu din yuli nyɛ "lower-alpha", ka lee bi saɣiritiri $It;references group ="lower-alpha"/> tuka maa bon nya

- Pages with script errors

- Peejinima din kundivira bi viɛla

- CS1 French-language sources (fr)

- CS1: long volume value

- CS1 German-language sources (de)

- CS1 Latin-language sources (la)

- Wikipedia articles needing page number citations from November 2014

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Pages using PMID magic links

- Articles containing Old English (ca. 450-1100)-language text

- Articles containing Latin-language text

- Articles with text in Nubian languages

- Articles containing Northern Sami-language text

- Articles containing Hungarian-language text

- Articles with text in Uncoded languages

- Articles containing Dutch-language text

- Articles containing Low German-language text

- Articles containing Swedish-language text

- Articles containing Norwegian-language text

- Articles containing Lithuanian-language text

- Articles containing Irish-language text

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2020

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- Articles with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Wikipedia pages with incorrect protection templates

- Good articles

- Use American English from January 2020

- All Wikipedia articles written in American English

- Use dmy dates from March 2024

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Domesticated animals

- Automatic taxobox cleanup

- Articles with 'species' microformats

- Taxoboxes with no color

- Taxonbars desynced from Wikidata

- Taxonbars on possible non-taxon pages

- Taxonbars with 20–24 taxon IDs

- Articles with BNE identifiers

- Pages with authority control identifiers needing attention

- Articles with BNF identifiers

- Articles with BNFdata identifiers

- Articles with GND identifiers

- Articles with J9U identifiers

- Articles with LCCN identifiers

- Articles with NDL identifiers

- Articles with NKC identifiers

- Articles with HDS identifiers

- Articles with NARA identifiers

- Cats

- English words

- Mammals described in 1758

- Animal models

- Articles containing video clips

- Felis

- Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus

- Cosmopolitan mammals

- Biŋkɔbigu

- Stubs

![The ancient Egyptians mummified dead cats out of respect in the same way that they mummified people.[113]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Louvre_egyptologie_21.jpg/300px-Louvre_egyptologie_21.jpg)